-

Francis Ellingwood Abbot

Francis Ellingwood Abbot (November 6, 1836-October 23, 1903), a founder of the Free Religious Association and first editor of the radical journal, the Index, developed an evolutionary philosophy of science. He yearned to free humankind from pre-scientific religions, believing that people could escape the trap of agnosticism by adopting his vision of free religion.

Francis, the third of six children of Unitarians Fanny Ellingwood Larcom and schoolmaster Joseph Hale Abbot, was born in Boston and educated in the classics at Boston Latin School. He graduated from the Harvard ranked number one in the class of 1859 and then married Katharine Fearing Loring. After studying for a year at the Harvard Divinity School, he completed his theological studies at Meadville Theological School, 1860-63. Here he experienced an intellectual revolution caused, in part, by his encounter with Darwin's theory of evolution. His theology began to evolve toward a new liberalism, based upon the scientific method.

In 1864 Abbot was ordained as minister of the Unitarian Church in Dover, New Hampshire. Within a year he began preaching on "Free Thinking," by which he meant that liberal Christians, employing complete intellectual freedom, should not be required to base their religion on the authority of Christ.

Two articles in the North American Review in 1864, "The Philosophy of Space and Time" and "The Conditioned and the Unconditioned," and another in The Christian Examiner in 1865, "Theism and Christianity," established Abbot as the first American philosopher to endorse Darwin's theory of evolution. To him, natural law and evolutionary adaptation were the foundations of "the unity of the universe, the mutual harmony of all facts and truths."

Abbot believed that philosophy and theology would each have to adapt to science. He thought that the community of nature, embracing both God and humans, could most fruitfully be explored using the scientific method. However, this required considering the purview of science as including the spiritual as well as the physical side of reality. For he believed that the human beings have a worshiping nature. He hoped that an extended definition of science, incorporating religion and theology, would eliminate what had become the traditional conflict between science and religion.

Although Abbot did not attend the organizational meeting of the National Conference of Unitarian Churches of 1865, he was distressed by the Constitutional preamble which committed Unitarians to be "disciples of the Lord Jesus Christ" because he felt it denied free inquiry. The following year he, with William. James Potter and others, attempted to have the preamble removed. Their failure led Abbot to resign from the Unitarian ministry and, in 1867, to join with Potter in organizing and writing the constitution for the Free Religious Association (FRA). The purpose of this new organization was "to promote the interest of pure religion, to encourage the scientific study of theology, and to increase fellowship in the spirit, (while leaving) each individual responsible for his own opinions alone and affect in no degree his relations to other Associations."

Abbot resigned his Dover Unitarian pulpit in 1868. Although retained for a while by a radical faction which split off from the church and was organized as an "Independent" society, by a ruling of the New Hampshire Supreme Court, he and his supporters, as non-Christians, were forbidden to use the church building.

In 1869 Abbot became the minister of the Unitarian Society of Toledo, Ohio. He made it a condition of his employment that the Society withdraw from the National Conference and change its name from Unitarian to Independent. As his sermons were really philosophical essays and his pastoral style was negligent, the congregation dwindled in size and, in 1872, stopped paying his salary. This settlement confirmed his unsuitability as a parish minister. While in Toledo, in 1870, he founded the Index, a weekly magazine with a radical religious and social philosophy. From its inception the Index functioned as the voice of the FRA.

After attending an 1872 convention advocating the Christianization of the United States Constitution, he became more than ever convinced that America was in bondage to Christianity, a religious philosophy which he believed could not provide a satisfactory foundation for the scientific world. In 1873 Abbot moved the Index to Boston, where he used it to call for the organization of Liberals Leagues all across America. These Leagues met in Philadelphia in 1876 and formed the National Liberal League. Abbot was elected its permanent president. In 1877, with more than fifteen hundred in attendance, the Congress of the League nominated Robert Ingersoll for President of the United States and Abbot for Vice President. He withdrew from the League the following year in protest over its congress's vote to campaign to repeal the Comstock laws.

Abbot's social philosophy shared in the nineteenth century ideal of the unity and fellowship of all humankind. His faith in the possibility of this fellowship was based on his faith in the unity of the Universe. He believed that an eternal harmony exists in nature. The challenge was to reorganize civilization so this harmony—based on the principles of freedom, truth, and equal rights for all people—would be reflected in society and in individuals. Accordingly, the welfare of society is secured by the welfare of each of its members. He thought it the duty of each person to make society more moral, just as it is the duty of society to develop each individual through adequate moral education. If this reciprocal duty is not fulfilled, he believed, natural law is violated and, consequently, the social organism is penalized. For a person's organic moral nature requires him or her to seek a balance between life for self and life for others. Thus, in order to enhance the development of individuals, Abbot felt that it was necessary to reorganize society on the basis of love, righteousness, and truth. Free Religion aimed to work for such a reorganized society by deepening "human effort to realize this ideal, both in the individual and in society, through the attainment of larger truth than the world has yet known, grander virtue than men have ever practiced, wiser and purer and freer social conditions than have ever yet existed."

Abbot argued that most of the evils that afflict society are preventable and unnecessary. He blamed Christianity for its postponement of "the very hope of universal reform to another world." He felt that Free Religion, having rejected superstition, dogmatism, and ecclesiasticism, offered a better method for social reform because its adherents realized that intelligent human effort, cooperating with nature and evolution and having faith in people, could bring about necessary reform in this world. Considering the power of the universal laws of nature and frailty of human efforts, he was nevertheless not optimistic about the future.

Abbot considered universal education the primary way to permanently elevate the condition of humanity. He claimed that for education to function as an effective method of reform, Free Religion must attack Christianity. For "notwithstanding its partial good influence in some respects, [Christianity remains] the most formidable and stubborn obstacle of social reform." He rejected individualism and the authority of private judgment in thought and action and contended that the scientific method should serve as the supreme authority in moral issues. Our judgments, he thought, ought to be guided by the authority of universal reason or the "Consensus of the Competent." The competent would be those who proved themselves to be such, to the satisfaction of humankind, by their combined intelligence and virtue. This consensus represents an evolving enlightened public opinion. In addition, the all-conquering scientific method would continue to provide direction to the Consensus of the Competent, helping in the growth of their understanding.

Abbot contended that some moral progress was perceptible, as shown, for example, in the United States Constitution's establishment of equal rights and the separation of Church and State. He explained: "It is not science alone that advances; it is not merely human intellect, but Man himself, that improves—Man with his feet in the mire and his head in the skies—Man, armed with a strength of brain that tames the wild forces of material Nature, and crowned with a conscience that makes him one with the Open Secret of the Universe." He considered the moral advance of humankind to be incomplete, however. There remained, he believed, a profound need in the Republic for more education in order to increase virtue. He thought it not enough for a person to improve his or her social and political surroundings. Each person, encouraged and aided by the educational process, might benefit by an increasing self-understanding as a self-governing being consecrated to higher and nobler aims useful to humanity. In his opinion Free Religion provided the social philosophy which best supported the continued moral progress of humanity.

In 1880 Abbot retired as editor of The Index (Potter replaced him) to study philosophy at Harvard University. It was his ambition to write a thesis would give philosophy a new direction for the next one hundred years. He was succesful, at least, in academe. Shortly before he graduated in 1881, William James came to his house to tell him he had taken the "degree by storm." Having a Ph.D. did not, however, open up any splendid teaching opportunities. As a consequence, he and his family continued to struggle economically. He taught at a boy's school in Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1881-92.

In 1885 Abbot wrote Scientific Theism. The book, which was also translated into German, was reviewed widely and considered a significant contribution to American philosophy. Charles Peirce, in the Nation, called it a "scholarly piece of work, doing honor to American thought."

In Scientific Theism, Abbot described what he called Relationalism, or Scientific Realism, a philosophy that he believed to be novel. He based Relationism on the following principles: 1. Relations are absolutely inseparable from their terms. 2. The relations of things are absolutely inseparable from the things themselves. 3. The relations of things must exist where the things themselves are, whether objectively in the cosmos or subjectively in the mind. 4. If things exist objectively, their relations must exist objectively; if their relations are merely subjective, the things themselves must be merely subjective. 5. There is no logical alternative between affirming the objectivity of relations in and with that of things, and denying the objectivity of things in and with that of relations.

Abbot spelled out the implications for religion of scientific realism. He portrayed nature as being born "in the eternally creative unity of Being and Thought." This meant that the universe, and all being, can be made intelligible by the tools provided by the scientific method. Consequently, he thought that whatever was currently unknown is knowable per se. He explained: "It is the great merit of new Scientific Realism to treat things and relations as two totally distinct orders of objective reality, indissolubly united and mutually dependent, yet for all that utterly unlike in themselves."

Abbot's Scientific Theism required teleology, a study of the end towards which all things tend: "Teleology is the very essence of purely spiritual personality; it presupposes thought, feeling, and will; it is the decisive battleground between the personal and impersonal conceptions of the universe." He thought that it is through understanding purpose in nature that human beings are able to recognize the purely spiritual personality that is God. The universe can be described, according to Abbot, as nature's process of self-evolution in time and space, or as the creative life of God.

In 1890 Abbot's The Way Out of Agnosticism, Or the Philosophy of Free Religion was published. By this time had also finished the outline of a projected two-volume work, The Syllogistic Philosophy, Or Prolegomena to Science. In 1893 his wife Katie and his friend William Potter died. Although the National Unitarian Conference adopted a new constitution, relegating the 1865 preamble to the status of a historical statement, his grief over these deaths and the rejection he still felt strongly made it impossible for him to return to Unitarianism. In 1903, upon completing The Syllogistic Philosophy, Abbot took a large dose of sleeping pills and died upon his wife's grave.

The Francis Ellingwood Abbot Papers, including, diaries, lecture notes, correspondence, writings, photographs, and family papers are in the Harvard Archives and in the archives at the Andover-Harvard Theological Library, Cambridge, Massachusetts. In addition to his books Abbot wrote a great many articles in the Index and a few in other publications, including the Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Free Religious Association and the Christian Examiner. His essays are gathered in W. Creighton Peden and Everett J. Tarbox, The Collected Essays of Francis Ellingwood Abbot, 4 volumes (1996). This also contains a bibliography of his articles. W. Creighton Peden, The Philosopher of Free Religion (1992) is a biography and a study of Abbot's thought. See also William J. Potter, The Free Religious Association: Its Twenty Five Years And Their Meaning (1892).

Article by Creighton Peden - posted May 14, 2009All material copyright Unitarian Universalist History & Heritage Society (UUHHS) 1999-2016

2016  votre commentaire

votre commentaire

-

Francis Ellingwood Abbot

Francis Ellingwood Abbot (6 novembre 1836 – 23 octobre 1903), l'un des fondateurs de la Free Religious Association et le premier rédacteur en chef de la revue radicale, l'Index, a développé une philosophie évolutive de

la science. Il aspirait à libérer l'humanité des religions pré-scientifiques, croyant que les gens pouvaient échapper au piège de l'agnosticisme en adoptant sa vision de la religion libre.

la science. Il aspirait à libérer l'humanité des religions pré-scientifiques, croyant que les gens pouvaient échapper au piège de l'agnosticisme en adoptant sa vision de la religion libre.Francis, le troisième des six enfants des unitariens Fanny Ellingwood Larcom et du pédagogue Joseph Hale Abbot, est né à Boston et a été instruit dans les classiques à Boston Latin School. Il a été diplômé d'Harvard et classé numéro un dans la classe de 1859, puis épousa Katharine Craignant Loring. Après avoir étudié pendant un an à la Harvard Divinity School, il a terminé ses études théologiques à l'école théologique de Meadville, de 1860 à1863. Ici, il a connu une révolution intellectuelle causée, en partie, par sa rencontre avec la théorie de l'évolution de Darwin. Sa théologie a commencé à évoluer vers un nouveau libéralisme, sur la base de la méthode scientifique.

En 1864, Abbot a été ordonné ministre de l'église unitarienne de Dover, dans le New Hampshire. En un an, il a commencé à prêcher sur la ‟ Free Thinking ″, (libre pensée) par laquelle il voulait dire que les chrétiens libéraux, employant la liberté intellectuelle complète, ne devaient pas être tenus de fonder leur religion sur l'autorité du Christ.

Deux articles dans la North American Review en 1864, ‟ La philosophie de l'espace et du temps ″ et ‟ Le conditionnel et l'inconditionnel″, et un autre dans l'examinateur Christian en 1865, ‟ théisme et le christianisme ″, établissant Abbot comme le premier philosophe américain à appuyer la théorie de l'évolution de Darwin. Pour lui, la loi naturelle et l′adaptation évolutive étaient les fondements de ‟ l'unité de l'univers, l'harmonie mutuelle de tous les faits et les vérités.″

Abbot croyait que la philosophie et la théologie auraient chacune à s′adapter à la science. Il pensait que la communauté de la nature, englobant à la fois Dieu et l'homme, pouvait très utilement être explorée à l'aide de la méthode scientifique. Cependant, cela nécessite l'examen de la compétence de la science comme incluant le spirituel aussi bien que le côté physique de la réalité. Car il croit que les êtres humains ont une nature cultuelle. Il espérait qu'une définition élargie de la science, incorporant la religion et la théologie, éliminerait ce qui était devenu le conflit traditionnel entre la science et la religion.

Bien qu′Abbot n'a pas assisté à la réunion d'organisation de la conférence nationale des églises unitariennes de 1865, il a été affligé par le préambule constitutionnel qui disait que les unitariens sont des ‟ disciples du Seigneur Jésus-Christ ″, car il estimait qu'il niait le libre examen. L'année suivante, avec William. James Potter et d'autres, ils ont tenté que le préambule soit retiré. Leur échec a conduit Abbot à démissionner du ministère unitarien et, en 1867, de se joindre à Potter pour organiser et rédiger la constitution de la Free Religious Association (FRA). Le but de cette nouvelle organisation était ‟ de promouvoir l'intérêt de la religion pure, d'encourager l'étude scientifique de la théologie, et d'accroître la communion dans l'esprit, (tout en laissant) chaque individu responsable seul de ses propres opinions et avec aucune incidence sur le degré de ses relations avec d'autres associations."

Abbot a démissionné de sa chaire unitarienne de Dover en 1868. Bien que retenu pendant un certain temps par une faction radicale qui était séparée de l'église et organisée comme une société ‟ indépendante ″, par une décision de la Cour suprême du New Hampshire, lui et ses partisans, comme non-chrétiens, ont été interdits d'utiliser le bâtiment de l'église.

En 1869, Abbot est devenu le ministre de la société unitarienne de Toledo, en Ohio. Il a fait une condition de son emploi que la société se retire de la conférence nationale et change son nom d′Unitarienne en Indépendante. Comme ses sermons étaient vraiment des essais philosophiques et son style pastoral négligent, la congrégation diminua en nombre et, en 1872, cessa de lui payer son salaire. Ce règlement a confirmé son inaptitude en tant que ministre de la paroisse. Alors à Tolède, en 1870, il a fondé l'Index , un magazine hebdomadaire avec une philosophie religieuse et sociale radicales. Depuis sa création , l'index fonctionnait comme la voix de la FRA.

Après avoir assisté à une convention en 1872 préconisant la christianisation de la Constitution des États - Unis, il est devenu plus que jamais convaincu que l'Amérique était dans la servitude au christianisme, une philosophie religieuse dont il croyait qu′elle ne pouvait pas fournir une base satisfaisante pour le monde scientifique. En 1873, Abbot a déplacé l′Index à Boston, où il l'a utilisé pour appeler à l'organisation des ligues des libéraux à travers l'Amérique. Ces ligues se sont réunies à Philadelphie en 1876 et ont formé la Ligue nationale libérale. Abbot a été élu président permanent. En 1877, avec plus de quinze cents personnes présentes, le Congrès de la Ligue a nommé Robert Ingersoll pour le président des États-Unis et Abbot le vice-président. Il se retira de la Ligue l'année suivante pour protester contre le vote de son congrès à la campagne pour abroger les lois de Comstock.

La philosophie sociale d′Abbot partagée au XIXe siècle était sur l′idéal de l'unité et de la communion de toute l'humanité. Sa foi dans la possibilité de cette communion était basée sur sa foi en l'unité de l'univers. Il croyait qu'une harmonie éternelle existe dans la nature. Le défi consistait à réorganiser la civilisation donc sur les principes de la liberté, de la vérité, et de l'égalité des droits pour tous et cette base d′égalité entre les gens se refléterait dans la société et les individus. En conséquence, le bien-être de la société est assurée par le bien-être de chacun de ses membres. Il pensait que le devoir de chaque personne est de rendre la société plus morale, tout comme c′est du devoir de la société de développer chaque individu par l'éducation morale adéquate. Si cette obligation réciproque n′est pas remplie, il croyait, que la loi naturelle est violée et, par conséquent, l'organisme social est pénalisé. Car la nature morale biologique d'une personne exige de lui ou d′elle à rechercher un équilibre entre la vie personnelle et la vie des autres. Ainsi, afin d'améliorer le développement des individus, Abbot a estimé qu'il était nécessaire de réorganiser la société sur la base de l'amour, la justice et la vérité. La religion gratuite destinée à travailler pour une telle société réorganisée par l'approfondissement de ‟ l'effort humain pour réaliser cet idéal, à la fois dans l'individu et dans la société, à travers la réalisation d'une plus grande vérité que le monde n'a pas encore connue, de la plus grande vertu que les hommes ont déjà pratiquée et des conditions sociales sages, plus pures et plus libres qui n'ont jamais encore existées.″

Abbot a fait valoir que la plupart des maux qui affligent la société sont évitables et inutiles. Il a accusé le christianisme dans son report sur ‟ l'espoir même de la réforme universelle pour un autre monde.″ Il a estimé que la Religion libre, après avoir rejeté la superstition, le dogmatisme et l′ecclésiale, offre une meilleure méthode pour la réforme sociale parce que ses adhérents ont réalisé que l'effort humain intelligent, coopérant avec la nature et l'évolution et tout ayant foi dans les gens, pourrait aboutir à une réforme nécessaire dans ce monde. Compte tenu de la puissance des lois universelles de la nature et de la fragilité des efforts humains, il était néanmoins pas optimiste quant à l'avenir.

Abbot considérait l'éducation universelle le principal moyen pour élever en permanence l'état de l'humanité. Il a affirmé que l'éducation fonctionne comme une méthode efficace de réforme. La libre religion doit attaquer le christianisme. Car ‟ malgré sa bonne influence partielle à certains égards, [le christianisme reste] l'obstacle le plus redoutable et tenace de la réforme sociale.″ Il a rejeté l'individualisme et l'autorité du jugement privé dans la pensée et l'action et a soutenu que la méthode scientifique devrait servir d'autorité suprême dans les questions morales. Nos jugements, pensait-il, doivent être guidés sur l'autorité de la raison universelle ou le ‟ Consensus de compétente. ″ La compétence serait à ceux qui s'avérèrent être tel, pour la satisfaction de l'humanité, par leur intelligence et vertu combinées. Ce consensus représente une opinion publique éclairée en évolution. En outre, la méthode scientifique conquérante continuerait à fournir des directives du consensus de compétente, contribuant à la croissance de leur compréhension.

Abbot a soutenu que certains progrès moraux était perceptibles, comme le montre, par exemple, dans l'établissement de la Constitution des États-Unis quant à l′égalité des droits et la séparation de l’Église et de l’État. Il a expliqué: ‟ Ce n′est pas la science seule qui avance, ce n′est pas non plus seulement l'intellect humain, mais homme lui-même, qui améliore - l′Homme avec ses pieds dans la boue et la tête dans le ciel - l′Homme, armé d'une force du cerveau qui apprivoise les forces sauvages de la nature matérielle, et couronné d'une conscience qui le fait un avec le secret ouverts de l'univers. ″ Il considérait l'avance morale de l'humanité pour être cependant incomplète. Il restait, selon lui, un besoin profond de la République pour plus d'éducation afin d'augmenter la vertu. Il pensait qu'il ne suffit pas à une personne d'améliorer son environnement social et politique. Chaque personne qui est encouragée et aidée par le processus éducatif, pourrait bénéficier d'une augmentation de la compréhension de soi en tant qu′autonome étant consacrée à la hausse et aux plus nobles objectifs utiles pour l'humanité. A son avis, la religion libre à condition que la philosophie sociale, qui a le mieux soutenu le progrès moral de l'humanité, continue.

En 1880, Abbot a pris sa retraite en tant que rédacteur de l'indice (Potter l' a remplacé) pour étudier la philosophie à l'université d′Harvard. Son ambition était d'écrire une thèse qui donnerait à la philosophie une nouvelle direction pour les cent prochaines années. Il y a réussi, au moins, dans le milieu universitaire. Peu avant, il a été diplômé en 1881, William James est venu à sa maison pour lui dire qu'il avait pris le ‟ degré par la tempête. ″ Avoir un doctorat n'a pas, cependant, ouvert toutes les possibilités des enseignements splendides. En conséquence, lui et sa famille continuèrent à lutter économiquement. Il a enseigné à une école pour garçons à Cambridge, dans le Massachusetts, de 1881 à 1892.

En 1885, Abbot a écrit théisme scientifique . Le livre, qui a également été traduit en allemand, a été examiné et largement considéré comme une contribution importante à la philosophie américaine. Charles Peirce, dans la Nation , l′a appelé un ‟ morceau scientifique du travail, faisant honneur à la pensée américaine. ″

Dans Théisme Scientifique, Abbot décrit ce qu'il a appelé le relationalisme, ou le réalisme scientifique, une philosophie qu'il croyait être nouvelle. Il a fondé le relationisme sur les principes suivants: 1. Les relations sont absolument inséparables de leurs termes. 2. Les rapports des choses sont absolument inséparables des choses elles-mêmes. 3. Les rapports des choses doivent exister où les choses elles-mêmes sont, que ce soit objectivement dans le cosmos ou subjectivement dans l'esprit. 4. Si les choses existent objectivement, leurs relations doivent exister objectivement; si leurs relations sont purement subjectives, les choses elles-mêmes doivent être purement subjectives. 5. Il n'y a pas d'alternative logique entre l'affirmation de l'objectivité des relations dans et avec celle des choses, et niant l'objectivité des choses dans et avec celle des relations.

Abbot précisait les implications pour la religion du réalisme scientifique. Il dépeint la nature comme étant née ‟ dans l'unité éternellement créatrice de l'être et la pensée. ″ Cela signifiait que l'univers, et tout être, peut être intelligible par les outils fournis par la méthode scientifique. Par conséquent, il pensait que tout ce qui était actuellement inconnu est connaissable en soi. Il a expliqué: ‟ C′est le grand mérite de nouveau réalisme scientifique de traiter les choses et les relations que deux ordres totalement distincts de la réalité objective, indissolublement unis et mutuellement dépendants, mais pour tout ce qui tout à fait la différence en eux-mêmes. ″

Le théisme scientifique d′Abbot nécessite la téléologie, une étude de la fin vers laquelle toutes les choses tendent: ‟ La téléologie est l'essence même de la personnalité purement spirituelle, elle suppose la pensée, le sentiment, et la volonté, elle est le champ de bataille décisif entre les conceptions personnelles et impersonnelles de l′univers. ″ Il pensait que c′est par la compréhension du but dans la nature que les êtres humains sont capables de reconnaître la personnalité purement spirituelle qui est Dieu. L'univers peut être décrit, selon Abbot, que le processus de la nature de l'auto-évolution dans le temps et dans l'espace, ou comme la vie créatrice de Dieu.

En 1890, The Way Out of Agnosticism, Or the Philosophy of Free Religion (La sortie de l′agnosticisme, Ou la philosophie de la religion libre) a été publié. A cette époque, il avait également terminé l'ébauche d'un ouvrage en deux volumes projetés, La syllogistique philosophie ou Prolégomènes à la science . En 1893, sa femme Katie et son ami William Potter sont morts. Bien que la Conférence nationale unitarienne adopta une nouvelle constitution, reléguant le préambule 1865 à l'état d'une déclaration historique, sa douleur sur ces décès et le rejet qu′il ressentait encore fortement, lui rendait impossible de revenir à l'unitarisme. En 1903, après avoir terminé la philosophie syllogistique, Abbot prit une grande dose de somnifères et mourut sur la tombe de sa femme.

*Le Francis Ellingwood Abbot Papers, y compris, agendas, notes de cours, de la correspondance, des écrits, des photographies et des papiers de famille sont dans les Archives d′Harvard et dans les archives à la Bibliothèque Théologique Andover-Harvard, Cambridge, Massachusetts. En plus de ses livres Abbot a écrit un grand nombre d'articles de l'indice et quelques-uns dans les autres publications, y compris les travaux de la Réunion annuelle de l'Association religieuse libre et l'examinateur Christian . Ses essais sont rassemblés dans W. Creighton Peden et Everett J. Tarbox, The Collected Essays de Francis Ellingwood Abbot , 4 volumes (1996). Il contient également une bibliographie de ses articles. W. Creighton Peden, Le Philosophe de Free Religion (1992) est une biographie et une étude de la pensée d′abbot. Voir aussi William J. Potter, L'Association religieuse libre: Ses vingt - cinq ans et leur signification . (1892)

Article par Creighton Peden - publié le 14 mai 2009

the Dictionary of Unitarian and Universalist Biography, an on-line resource of the Unitarian Universalist History & Heritage Society. http://uudb.orgtraduit de l'anglais au français par DidierLe Roux

Retour page d'accueil

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Le Roux Didier- Unitariens - © Depuis 2006 - Tous droits réservés

"Aucune reproduction, même partielle, autres que celles prévues à l'article L 122-5 du code de la propriété intellectuelle, ne peut être faite de ce site sans l'autorisation expresse de l'auteur ".

votre commentaire

votre commentaire

-

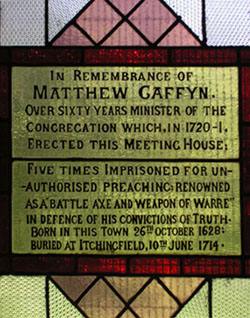

Matthew Caffyn (bap. October 26, 1628, bur. June 1714), an important early British General Baptist preacher and evangelist, was an influential antitrinitarian.

Matthew Caffyn (bap. October 26, 1628, bur. June 1714), an important early British General Baptist preacher and evangelist, was an influential antitrinitarian.Matthew was the seventh son of Thomas and Elizabeth Caffyn. According to family tradition, Elizabeth was a direct descendant of a martyr of the Marian persecution, possibly John Forman, who was burnt at East Grinstead in 1556. Thomas Caffyn was employed by the Onslow family, who owned Drungewick Manor, near the border of Sussex and Surrey. When Matthew was about 7, the head of the Onslow family adopted him as a companion for his own son Richard. The two boys were educated at a grammar school in Kent and, then, in 1643, sent to All Soul's College, Oxford to study for the Church of England ministry.

A conscientious and able student of ancient languages, scriptures, and theology, Caffyn came to question both infant baptism and the Trinity and debated these doctrines with his professors. But this series of discourses failed to resolve matters to either party's satisfaction. Unable to convince Caffyn as to the validity of traditional belief, the university authorities tried unsuccessfully to induce him suppress his own views. He responded to their challenges 'patiently, clearly and fearlessly'. When, as became inevitable, he was expelled from Oxford, he left 'with an easy conscience'.

In 1645 Caffyn, now 17, returned to Horsham, his future uncertain. Nevertheless his relationship with his patron remained firm, and it was perhaps thanks to Onslow that he was installed at Pond Farm in Southwater. He lived and worked the land there and at another local farm, in Broadbridge Heath, during the remainder of his life.

Soon after he returned to Horsham, Caffyn was appointed assistant to the local General Baptist minister, Samuel Lover. During this period their religious meetings were held in private houses. Caffyn's campaigning vigour brought about a significant increase in local adherents, and, perhaps as early as 1648, he took over the ministry from Lover. By the age of 25 he had become a denominational leader, and had been appointed a 'messenger'. He was one of the few General Baptist leaders who had received any university training.

At the same time he was active as a preacher and propagandist in the towns and villages round about. He engaged in vigorous debate and dispute with the Quakers, for whom Horsham had become an important centre (William Penn had a house nearby at Warminghurst), and there is a famous account of an encounter in 1655 when Thomas Lawson and John Slee, two Friends from the north, disputed doctrine with him. The result of their debates was a pamphlet by Lawson entitled An Untaught Teacher witnessed against (1655) and Caffyn's Deceived and Deceiving Quakers Discovered, their Damnable Heresies, Horrid Blasphemies, Mockings, Railings (1656). Caffyn also opposed George Fox, when he held a meeting in the area.

Caffyn's increasing influence, through persuasive oratory and skill as a polemicist, was felt throughout Sussex, Kent, Surrey, Hampshire and further afield. There was, for example, a public debate between Caffyn and the Anglican minister at Waldron parish church, as a result of which two local men were converted, one of whom became pastor to the Baptist congregation at Warbleton. The vicar of Henfield challenged Caffyn to a public debate in Latin, in the presence of other ministers, hoping to show him up, but Caffyn's university education stood him in good stead and he won the day. His supporters thereafter called him 'their battle axe and weapon of warre'.

Caffyn fell out with Richard Haines, a member of his congregation who been close to him for a long time. Haines, a successful farmer, social reformer, inventor and author, promoted schemes for prevention of poverty and setting up 'working alms houses', invented a new way of cleaning clover seed from the husk, and applied for a patent for making 'cider-royal'. These ventures brought Haines into contact with men of influence, such as the Earl of Shaftesbury, and elicited disapproval from Caffyn, who held that patents were covetous and was uncomfortable with Haines's entry into a social milieu which he considered too far removed from the 'truly pious'. In 1672 Caffyn excommunicated Haines on the grounds that his greed was a cause of scandal and reflected badly on the church. The following year Haines appealed formally to the General Assembly. The matter was finally resolved in 1680, when the Assembly reversed the excommunication and ordered Caffyn to rescind it.

In 1691 Joseph Wright denounced Caffyn to the General Assembly for stating, in a private conversation, objections to parts of the Athanasian creed. This, Wright claimed, amounted to denying both the divinity and the humanity of Christ. Accordingly, he moved for Caffyn's excommunication. But Caffyn's defence satisfied the Assembly, as it did when the matter was raised again in 1693, and later in 1698, 1700, and 1702. He took the Socinian view, which denied Christ's deity. When the Assembly refused to vote for Caffyn's expulsion, a rival Baptist General Association was formed. For many years Caffyn's Unitarian 'heresy' was a continual source of debate. During his own lifetime his adherents were known as 'Caffynites'. A pamphlet by Christopher Cooper of Ashford quoted one of his opponents who called his views 'a fardel of Mahometanism, Arianism, Socinianism and Quakerism'.

During the period of the Restoration (1660-1688) the British Parliament passed several Conventicle Acts, attempting to suppress non-conformist worship. The first act, in 1664, made it illegal for more than 5 persons over the age of 16 to assemble together for worship, except according to the rites of the Book of Common Prayer. A more severe act was passed in 1670, whereby a justice of the peace could convict without evidence if he believed a conventicle had been held. This suppression of Baptists and other dissenters continued until the 1689 Toleration Act, an important step towards freedom of worship. During the time the Conventicle Acts were in force, Caffyn was fined and had his livestock seized. He was imprisoned five times, once for about a year in Newgate, 'where he lay some time in a loathsome dungeon, and hardly escaped with his life', until the Onslow family obtained his release. He also spent time in Maidstone and Horsham gaols.

In 1653 Caffyn married Elizabeth Jeffrey, from another General Baptist family, whom he met while preaching in Kent. They had 8 children: Joseph, Daniel, Sarah, Benjamin, Thomas, Stephen, Jacob and Matthew. Caffyn was a frugal man, and managed to support his growing family with little help from his church. During his last imprisonment he was supported by the industry of his wife, who remained productive at her spinning wheel. She died in 1693. Matthew the younger was ordained a General Baptist elder by his father in 1710, and, together with Thomas Southon, took over the Horsham ministry. It is said that Matthew the elder was buried under an old yew tree in Itchingfield churchyard, but any stone that may have marked his grave is now gone. His only remaining memorial is a window dedicated to him in the Unitarian church in Worthing Road, Horsham.

Among Caffyn's other publications are Faith in God's Promises the Saint's Best Weapon (1661), Envy's Bitterness Corrected (1674), A Raging Wave Foaming Out its Own Shame (1675), The Great Error and Mistake of the Quakers (n.d.), and The Baptist's Lamentation (n.d.). Sources of information on Caffyn, his contemporaries, and his church include Mark Anthony Lower, The Worthies of Sussex (1865); Florence Gregg, Matthew Caffin, a Pioneer of Truth (1890); Charles Haines, Complete Memoir of Richard Haines, 1633-1685 (1899); Emily Kensett, History of The Free Christian Church, Horsham (1921); John Caffyn, Sussex Believers (1988); Victoria County History of Sussex, Vol VI, Pt II; and Dictionary of National Biography (2000).

Article by Brian Slyfield - posted July 26, 2009Main Page | About the Project | Contact Us | Fair Use Policy

All material copyright Unitarian Universalist History & Heritage Society (UUHHS) 1999-2016

votre commentaire

votre commentaire

-

Matthew Caffyn

Matthew Caffyn (26 octobre 1628 - Juin 1714), était un important des premiers prédicateurs et évangélistes Baptistes Généraux britaniques et aussi un anti-trinitaire influent.

Matthew était le septième fils de Thomas et Elizabeth Caffyn. Selon la tradition de la famille, Elizabeth était un descendant direct d'un martyr de la persécution Marian, peut-être John Forman, qui a été brûlé à East Grinstead en 1556. Thomas Caffyn a été employé par la famille Onslow, qui possédait Drungewick Manor, près de la frontière du Sussex et du Surrey. Lorsque Matthew avait environ 7 ans, le responsable de la famille Onslow l'a adopté comme un compagnon pour son propre fils Richard. Les deux garçons ont été éduqués dans une école de grammaire dans le Kent et, puis, en 1643, il a été envoyé au Collège All Soul à Oxford pour étudier le ministère de l'Église d'Angleterre.

Un étudiant consciencieux et capable en langues ‟ anciennes ˮ, écritures et théologie, Caffyn est venu sur la question à la fois du baptême des enfants et la Trinité et débattit ces doctrines avec ses professeurs. Mais cette série de discours n'a pas réussi à résoudre les problèmes pour la satisfaction de l'une des parties. Incapable de convaincre Caffyn quant à la validité de la croyance traditionnelle, les autorités universitaires tentèrent en vain de lui faire supprimer ses propres vues. Il répondit à leurs défis ‟ patiemment, clairement et sans crainte. ˮ Lorsque, comme c'était devenu inévitable, il a été expulsé d'Oxford, et partit ‟ la conscience tranquille. ˮ

En 1645 Caffyn, maintenant âgé de 17 ans, retourna à Horsham, avec son avenir incertain. Néanmoins sa relation avec son patron est restée ferme, et c'est peut-être grâce à Onslow qu'il a été installé à Pond Farm dans Southwater. Il vécut et travailla la terre là-bas et à une autre ferme locale, Broadbridge Heath, pendant le reste de sa vie.

Peu après de temps qu'il soit revenu à Horsham, Caffyn a été nommé assistant du ministre baptiste général local, Samuel Amant. Pendant cette période, leurs réunions religieuses avaient lieu dans des maisons privées. la vigueur de la campagne de Caffyn entraîna une augmentation significative des adhérents locaux, et, peut-être dès 1648, il reprit le ministère de Lower. À l'âge de 25 ans, il était devenu un chef de file confessionnel, et avait été nommé un ‟ messager. ˮ Il était l'un des rares leaders des baptistes généraux qui avaient reçu une formation universitaire.

En même temps, il a été actif en tant que prédicateur et propagandiste dans les villes et les villages alentour. Il s'est engagé dans un débat vigoureux et contestait avec les Quakers, pour lesquels Horsham était devenu un important centre (William Penn avait une maison voisine à Warminghurst), et il y a un rapport célèbre d'une rencontre en 1655 lorsque Thomas Lawson et John Slee, deux amis du nord, contestaient la doctrine avec lui. Le résultat de leurs débats était une brochure de Lawson intitulée An Untaught Teacher witnessed against (1655) et de Caffyn Deceived and Deceiving Quakers Discovered, their Damnable Heresies, Horrid Blasphemies, Mockings, Railings (1656). Caffyn également s'opposa à George Fox, quand il tint une réunion dans la région.

L'influence de Caffyn qui augmentait, par l'éloquence persuasive et l'habileté comme polémiste, a été ressentie dans le Sussex, le Kent, le Surrey, le Hampshire et plus loin. Il y eut, par exemple, un débat public entre Caffyn et le ministre anglican à l'église paroissiale Waldron, à la suite duquel deux hommes locaux se sont convertis, dont l'un est devenu pasteur de la congrégation baptiste à Warbleton. Le vicaire de Henfield contesta Caffyn lors d'un débat public en latin, en présence d'autres ministres, dans l'espoir de lui démontrer, mais l'éducation de l'université de Caffyn le tenait en bonne place et il gagna ce jour. Ses partisans par la suite l'appelèrent ‟ leur hache de combat et arme de guerre. ˮ

Caffyn tomba avec Richard Haines, membre de sa congrégation qui a été près de lui pendant une longue période. Haines, un fermier prospère, réformateur social, inventeur et auteur, fit la promotion des programmes de prévention de la pauvreté et la mise en place le ‟ travaille d'aumônes pour les maisons ˮ, a inventé une nouvelle façon de nettoyer les graines de trèfle de la balle, et une demande de brevet pour la fabrication du 'cider-Royal'. Ces entreprises ont amené Haines à être en contact avec des hommes d'influence, comme le comte de Shaftesbury, et suscita la désapprobation de Caffyn, qui jugea que les brevets étaient cupides et était mal à l'aise avec l'entrée de Haines dans un milieu social qui lui paraissait trop loin du ‟ vraiment pieux. ˮ En 1672, Caffyn excommunia Haines au motif que son avidité était une cause de scandale et rejaillissait mal sur l'église. L'année suivante, Haines a fait appel officiellement à l'assemblée générale. La question a finalement été résolue en 1680, lorsque l'assemblée renversa l'excommunication et ordonna Caffyn de l'annuler.

En 1691, Joseph Wright dénonça Caffyn à l'assemblée générale pour avoir déclaré, dans une conversation privée, des objections à certaines parties du credo d'Athanase. A ceci, Wright revendiqua, et s'éleva à la fois pour nier la divinité et l'humanité du Christ. En conséquence, il demanda l'excommunication de Caffyn. Mais la défense de Caffyn convainquit l'assemblée, comme il l'a fait lorsque la question avait été soulevée à nouveau en 1693, et plus tard en 1698, 1700 et 1702. Il prit l'idée socinienne, qui niait la divinité du Christ. Lorsque l'assemblée refusa de voter pour l'expulsion de Caffyn, une association baptiste générale a été formée en opposition. Pendant de nombreuses années ‟ l'hérésie ˮ unitarienne de Caffyn a était une source continuelle de débat. Au cours de son vivant ses adhérents étaient connus comme ‟ Caffynites. ˮ Une brochure de Christopher Cooper d'Ashford a cité un de ses adversaires qui appelaient son point de vue 'un fardeau de mahométisme, d'arianisme, de socinianisme et de Quakerisme'.

Pendant la période de la Restauration (1660-1688) le Parlement britannique adopta plusieurs lois conciliabules, en essayant de supprimer les cultes non-conformistes. Le premier acte, en 1664, rendit illégal à plus de 5 personnes de plus de 16 ans de se rassembler pour le culte, sauf selon les rites du livre commun de prière. Un acte plus grave a été adopté en 1670, par lequel un juge de paix pouvait condamner sans preuve s'il croyait un conciliabule avait eu lieu. Cette suppression des baptistes et d'autres dissidents continua jusqu'à ce que la loi de Tolérance de 1689, une étape importante vers la liberté de culte. Pendant ce temps les actes de conciliabule étaient en vigueur, Caffyn a été condamné à une amende et son bétail saisi. Il a été emprisonné cinq fois, une fois pour environ un an à Newgate, 'où il se trouvait un peu de temps dans un cachot répugnant, et à peine il échappait de perdre sa vie', jusqu'à ce que la famille Onslow obtint sa libération. Il a également passé du temps dans les prisons de Maidstone et Horsham.

En 1653 Caffyn épousa Elizabeth Jeffrey, d'une autre famille baptiste générale, qu'il rencontra tout en prêchant dans le Kent. Ils ont eu 8 enfants: Joseph, Daniel, Sarah, Benjamin, Thomas, Stephen, Jacob et Matthew. Caffyn était un homme économe et réussit à soutenir sa famille grandissante avec le peu d'aide de son église. Lors de son dernier emprisonnement, il a été soutenu par le travail de sa femme, qui est resté productive à son rouet. Elle est morte en 1693. Matthew le plus jeune a été ordonné un ancien général baptiste par son père en 1710, et, en collaboration avec Thomas Southon, a repris le ministère Horsham. Il est dit que Matthieu l'aîné a été enterré sous un vieil arbre d'ifs dans le cimetière Itchingfield, mais toute pierre qui pourrait avoir marqué sa tombe a disparue maintenant. Il ne reste pour sa mémoire qu'une fenêtre qui lui est consacrée dans l'église unitarienne de Worthing Road, Horsham.

*Parmi les autres publications de Caffyn il y a : Faith in God's Promises the Saint's Best Weapon (1661), Envy's Bitterness Corrected (1674), A Raging Wave Foaming Out its Own Shame (1675), The Great Error and Mistake of the Quakers (n.d.), and The Baptist's Lamentation (n.d.). Sources d'informations sur Caffyn, ses contemporains, et son église incluent Mark Anthony Lower, The Worthies of Sussex (1865); Florence Gregg, Matthew Caffin, a Pioneer of Truth (1890); Charles Haines, Complete Memoir of Richard Haines, 1633-1685 (1899); Emily Kensett, History of The Free Christian Church, Horsham (1921); John Caffyn, Sussex Believers (1988); Victoria County History of Sussex, Vol VI, Pt II; and Dictionary of National Biography (2000).

Article par Brian Slyfield - Envoyé le 26 juillet, 2009

the Dictionary of Unitarian and Universalist Biography, an on-line resource of the Unitarian Universalist History & Heritage Society. http://uudb.orgtraduit de l'anglais au français par DidierLe Roux

Retour page d'accueil

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Le Roux Didier- Unitariens - © Depuis 2006 - Tous droits réservés

"Aucune reproduction, même partielle, autres que celles prévues à l'article L 122-5 du code de la propriété intellectuelle, ne peut être faite de ce site sans l'autorisation expresse de l'auteur ".

votre commentaire

votre commentaire

-

John Boyden

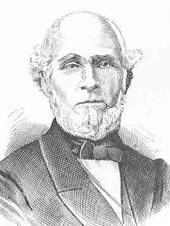

John Boyden (May 14, 1809-September 28, 1869), a Universalist minister, politician, and social reformer, was a disciple of Hosea Ballou and the longtime pastor of the First Universalist Church of Woonsocket, Rhode Island. He worked prominently there for public education, temperance, abolition, and new forms of medical treatment.

Born in Sturbridge, Massachusetts, John was the seventh of ten children born to farmers John and Elizabeth Boyden. He attended schools in Sturbridge and in nearby Brookfield and Dudley, Massachusetts. After finishing his education he taught in local schools while continuing to help his parents with their farm. At 14 he heard Hosea Ballou preach in Brookfield. A few years later, after another visit by Ballou to his area, he was converted to Universalism. In 1829 he quit teaching and was, for a year, a student for the ministry, living at Boston in the Ballou household. When Ballou sent him to preach his first sermon, he told him, "Be in earnest. Don't speak one word without making the people understand and feel that you believe it with all your heart."

Boyden's first settlements were at Berlin, Connecticut, 1832-36, and Dudley, Massachusetts, 1836-40. While in Connecticut he visited P. T. Barnum, in jail for libel. In Dudley he worked part-time for the Universalist church in Southbridge, Massachusetts, 1838-39, and served as a representative to the state legislature. He was called to be the first minister to Universalists in Woonsocket, Rhode Island in 1840. The Universalists there, who had been organized since 1834, had just erected their first church building. He served this church and the Woonsocket community until his death nearly thirty years later.

In a published sermon, The Dangerous Tendency of Partialism, 1843, Boyden likened anxiety over salvation, revivalism, and other "religious excitements" to alcoholism. Both practices, he reasoned, were dangerous to the health, and the consequent states of intoxicated illness were among the hells human beings create for themselves on earth. "Some persons are born again," he preached in 1847, "but only born to a few good things. They must grow-learn to do well-it is a track." The central idea of his life was "improvement": reform in every aspect of social and individual life.

As chair of the local Washingtonian Total Abstinence Society, Boyden campaigned for years against liquor licensing. In 1845 he was successful in getting local government to cease granting liquor licenses. Five years later he proposed a vigilance committee to help with the enforcement of these laws. After the failure of enforcement, in 1852 he backed the passage of prohibition modeled on the legislation adopted in Maine the year before. In order to keep this "Maine Law" in effect, in 1853 Boyden participated in a convention which organized a short-lived temperance party. As other issues came to the forefront during the 1850s, he found himself increasingly isolated within his community in his hard-line stance against the consumption of alcohol.

Boyden was much more successful in the organization and promotion of public school education in Woonsocket. He served on the local school committee, 1841-51, again later in the 1850s, and 1860-64; functioned as chief local publicist for Henry Barnard's program of statewide educational reform; backed the unification and standardization of local school districts, 1849; and helped organize the Cumberland and Smithfield Institute of Education, 1845, which provided teacher training. He is remembered in a local history written shortly after his death as a leading light "among those who have labored earnestly and wisely for the advancement of popular education in Woonsocket."

A local abolitionist leader, Boyden was a candidate for the United States House of Representatives on the Liberty Party ticket in 1847. He ran again, as a member of the Free Soil Party, in 1849. In the mid-1850s he was recruited by the Know-Nothing Party which in Rhode Island based much of its appeal on temperance and abolition. Although this may have been a case of "politics makes strange bedfellows," there were points of contact between the nativism of the Know-Nothings and Boyden's reform concerns. The influx of immigration that sparked nativist xenophobia was largely Roman Catholic, and Boyden was alarmed that Catholics often preferred not to send their children to public schools and that the drinking customs of these immigrants frustrated the temperance program. "Our country has many nationalities," Boyden said in an 1865 lecture, "Diversity in Unity," "but they ought to blend as rivers in a sea. The foreigner should be an American, with all the force of his nature. He should educate his children in our schools, preparing them to act the part of freemen. No man, foreign or native-born, should be allowed to cast a ballot who cannot read."

In 1854 Boyden, calling himself an independent, defeated a prominent local Democratic politician in a by-election for a seat in the Rhode Island General Assembly. The surprising result of this isolated contest was the first evidence of a new political phenomenon in the state. The following year the Know-Nothings won a landslide victory in the state election. Boyden was elected a state senator on the Know-Nothing/Free Soil ticket. As a senator he voted for a number of reforms, including constitutional amendments to provide a poll tax for public education and a 21 year residency requirement for citizenship. These amendments were later defeated by referendum. After the Know-Nothings (by that time called the American Party) fragmented over abolition, with the northern delegates walking out of their 1856 national convention, Boyden no longer ran for public office and became a supporter of the newly-founded Republican Party.

While making his pastoral rounds Boyden practiced homeopathic healing. He dispensed "little pills," nursed sick parishioners, and consulted with the local homeopathic physician. For these activities he was accused of being a "quack" by a local physician. Boyden, on the other hand, believed that the traditional forms of medicine used by the regular physician-blood-letting and dosing with mercury compounds-needed to be replaced by something new and improved. "What is the origin of 'quackery among the clergy' and others, if it is not quackery among physicians?" he asked the indignant doctor. "Your failures have driven the people to try experiments."

Boyden supported voting and property rights for women, shorter hours for mill workers, aid for the starving in Ireland, public libraries, prison reform, and kind treatment of animals. He strenuously opposed capital punishment. He admired his crusading neighbor to the north, Adin Ballou, leader of the utopian community at Hopedale, Massachusetts. The two exchanged ministerial services and Boyden often attended Ballou's lectures and Hopedale community events. Having attended the new meeting house dedication in Hopedale in 1860, Boyden praised the community for "striving to realize the angelic announcement of peace on earth and goodwill to men."

During his entire pastorate in Woonsocket Boyden was the chief officer of the Rhode Island Universalist State Convention-standing clerk, 1840-61, and, after the convention was reorganized, president, 1861-69. He gave the annual sermon at the United States Universalist General Convention held at Baltimore in 1844. Besides a number of tracts, Boyden published a Sunday School hymnal,The Eastern Harp, 1848. He and his congregation introduced public Christmas celebrations in Woonsocket in the 1850s.

Boyden married Sarah Church Jacobs in 1831. They had one son, John Richmond Boyden, who died in young adulthood. Struggling with chronic poor health, Boyden took a leave of absence for several months in 1857. Traveling in New Hampshire the Boydens visited a Shaker community and were impressed by "a serenity of countenance that indicates the peace of God in the soul." They did not sleep in the community, however, as there were separate accomodations for women and men: "not being prepared even for a temporary divorce, [we] sought and obtained very comfortable quarters with a private family nearby."

After Boyden died the Universalist church he had so long served held annual services at his grave. These regular commemorations persisted into the early 20th century.

The biographer of Hosea Ballou, Oscar Safford, included Boyden with Hosea Ballou 2d, Thomas Whittemore, and Lucius Paige in a chapter called "Spiritual Sons." "We know not who in his generation surpassed him in largeness of love-the Christian love which recognizes the Infinite in the finite, the Divine in the human, and feels another's joy and sorrow as its own," Safford wrote. "No name among those held in honor by the Universalist Church is regarded with more affection than John Boyden, the Christian pastor, who had a genius for loving."

A diary and other papers relating to John Boyden are in the archives of the First Universalist Church of Woonsocket, Rhode Island. The archives include typescript histories of the church and a transcription of "The 1847 Diary of Rev. John Boyden" with a biographical introduction by Peter Hughes and a transcribed collection including many Boyden items, "The First Universalist Church in the Woonsocket Patriot, 1837-1869." Boyden publications not already mentioned include Review of Rev. M. Hill's Sermon on "American Universalism" (1844), Review of a Tract Entitled "A Strange Thing" (1845), (with A. Abbott) Religious Bigotry (1845), and "The Reign of Christ" in The Christian Helper (1858). Other useful sources of primary information are the Rhode Island government records, at the State House in Providence, Rhode Island and issues of the Universalist Register (1841-70). There is an obituary in the 1870 issue. Oscard F. Safford included several pages on Boyden in Hosea Ballou: A Marvellous Life-Story (1889). Boyden is also mentioned in Erastus Richardson, History of Woonsocket (1876) and Charles Stickney, Know-Nothingism in Rhode Island (1894). See also John G. Adams, Fifty Notable Years (1883) and Peter Hughes, "Quackery among the Clergy: Medicine and Ministry in Conflict in 1848," Proceedings of the Unitarian Universalist Historical Society (1995).

Article by Peter Hughes - posted August 4, 2004All material copyright Unitarian Universalist History & Heritage Society (UUHHS) 1999-2016

_______  votre commentaire

votre commentaire

-

John Boyden

John Boyden (14 mai 1809- 28 septembre 1869), un ministre universaliste, homme politique et réformateur social, était un disciple de Hosea Ballou et le pasteur de longue date de la première église

universaliste de Woonsocket, dans le Rhode Island. Il a travaillé là par évidence à l'éducation du public, la tempérance, l'abolition, et de nouvelles formes de traitements médicaux.

universaliste de Woonsocket, dans le Rhode Island. Il a travaillé là par évidence à l'éducation du public, la tempérance, l'abolition, et de nouvelles formes de traitements médicaux.Né à Sturbridge, dans le Massachusetts, John était le septième des dix enfants nés des agriculteurs John et Elizabeth Boyden. Il a fréquenté les écoles à Sturbridge et dans les environs de Brookfield et Dudley, dans le Massachusetts. Après avoir terminé ses études, il a enseigné dans les écoles locales tout en continuant à aider ses parents à leur ferme. A 14 ans, il entendit Hosea Ballou prêcher dans Brookfield. Quelques années plus tard, après une autre visite de Ballou dans sa région, il a été converti à l′universalisme. En 1829, il quitta l'enseignement et en été, pendant un an, fut un étudiant pour le ministère, vivant à Boston dans la famille Ballou. Lorsque Ballou l′envoya prêcher son premier sermon, il lui dit: ‟ Sois bon. Ne dit pas un mot sans que les gens comprennent et sentent que tu crois de tout votre cœur. ˮ

Les premières installations de Boyden ont été à Berlin, Connecticut, 1832-1836, et Dudley, Massachusetts, de 1836-40. Alors que dans le Connecticut, il visita P.T. Barnum, en prison pour diffamation. Dans Dudley, il a travaillé à temps partiel pour l'église universaliste à Southbridge, Massachusetts, de 1838-1839, et servit comme un représentant à la législature de l'État. Il a été appelé pour être le premier ministre universalistes à Woonsocket, dans le Rhode Island en 1840. Les universalistes là-bas, qui étaient organisés depuis 1834, venaient d'ériger leur premier bâtiment pour église. Il servit cette église et la communauté Woonsocket jusqu'à sa mort près de trente ans plus tard.

Dans un sermon publié, The Dangerous Tendency of Partialism (La tendance dangereuse de la partialité), en 1843, Boyden a comparé l'anxiété sur le salut, le revivalisme, et d'autres ‟ excitations religieuses ˮ à l'alcoolisme. Ces deux pratiques, il pensait, sont dangereuses pour la santé, et les états qui en découlent de la maladie en état d'ébriété sont parmi les enfers créés par les humains eux-mêmes sur la terre. ‟ Certaines personnes sont nées de nouveau ˮ, il prêcha en 1847, ‟ mais seulement nées pour quelques bonnes choses. Elles doivent grandir pour apprendre à faire bien, c′est une piste. ˮ L'idée centrale de sa vie était ‟ amélioration ˮ: la réforme dans tous les aspects de la vie sociale et individuelle.

En tant que président de Washingtonian Total Abstinence Society, Boyden faisait campagne depuis des années contre les permis d'alcool. En 1845, il a réussi à obtenir du gouvernement local de cesser l'octroi de permis d'alcool. Cinq ans plus tard, il a proposé un comité de vigilance pour aider à l'application de ces lois. Après l'échec de l'exécution, en 1852, il a soutenu le passage de l'interdiction sur le modèle de la législation adoptée dans le Maine l'année précédente. Afin de maintenir cette ‟ loi Maine ˮ en effet, en 1853 Boyden a participé à une convention qui organisait une fête de la tempérance de courte durée. Comme d'autres problèmes sont venus à l'avant-garde dans les années 1850, il se trouva de plus en plus isolé au sein de sa communauté dans sa position de la ligne dure contre la consommation d'alcool.

Boyden a eu beaucoup plus de succès dans l'organisation et la promotion de l'éducation des écoles publiques à Woonsocket. Il a siégé au comité scolaire local, de 1841-1851, plus tard dans les années 1850 et de 1860 à 1864; et agissait en tant que chef de campagne locale pour le programme de Henry Barnard sur la réforme de l'éducation pour tout l'État; soutenait l'unification et la normalisation des districts scolaires locaux, en 1849. Il a aidé à organiser le Cumberland et Smithfield Institute of Education, 1845, qui fournissaient la formation des enseignants. Il se souvient d'une histoire locale écrite peu de temps après sa mort comme d′un phare ‟ parmi ceux qui ont travaillé sérieusement et à bon escient pour la promotion de l'éducation populaire à Woonsocket. ˮ

En tant qu′un leader abolitionniste local, Boyden a été candidat pour les United States House of Representatives pour le côté du Liberty Party en 1847. Il a couru à nouveau, en tant que membre du Free Soil Party, en 1849. Au milieu des années 1850, il a été recruté par le Know-Nothing Party qui dans le Rhode Island basait beaucoup son attrait sur la tempérance et l'abolition. Bien que cela puisse avoir été un cas de ‟ politique faisant d′étranges compagnons ˮ, il y avait des points de contact entre le nativisme du Know-Nothing Party et la réforme des préoccupations de Boyden. L'afflux de l'immigration qui déclenchait la xénophobie nativiste était en grande partie catholique romaine, et Boyden a été alarmé que les catholiques ont souvent préféré ne pas envoyer leurs enfants dans des écoles publiques et que les coutumes de consommation de ces immigrants empêchaient le programme de tempérance. ‟ Notre pays a beaucoup de nationalités ˮ, Boyden déclara dans une conférence de 1865, ‟ La diversité dans l'unité ˮ, ‟ mais elles doivent se fondre comme les rivières dans une mer. L'étranger doit être un américain, avec toute la force de sa nature. Il devrait éduquer ses enfants dans nos écoles, en les préparant à jouer le rôle des hommes libres. Aucun homme, étranger ou natif, ne doit être autorisé à voter s′il ne peut pas lire. ˮ

En 1854, Boyden, se disant indépendant, battit un homme politique démocrate local de premier plan dans une élection partielle pour un siège à l'assemblée générale de Rhode Island. Le résultat surprenant de ce concours isolé était la première preuve d'un nouveau phénomène politique dans l'État. L'année suivante, le Know-Nothings a remporté une victoire écrasante dans l'élection de l'Etat. Boyden a été élu sénateur de l’État sur le côté du Know-Nothing/Free Soil. En tant que sénateur, il vota pour un certain nombre de réformes, y compris les amendements constitutionnels pour fournir une taxe de scrutin pour l'éducation publique et une exigence de 21 ans de résidence pour la citoyenneté. Ces modifications ont ensuite été repoussées par référendum. Après le Know-Nothings (par ce temps appelé l′Américan Party) était fragmenté sur l'abolition, avec les délégués du Nord en dehors de leur congrès national de 1856, Boyden alors courut pour la fonction publique et devint un partisan du Parti Républicain nouvellement fondé.

Tout en faisant ses tournées pastorales Boyden pratiquait la guérison homéopathique. Il dispensait de ‟ petites pilules ˮ, soignant les paroissiens malades, et ils consultaient le médecin homéopathe local. Pour ces activités, il a été accusé d'être un ‟ charlatan ˮ par un médecin local. Boyden, d'autre part, a estimé que les formes traditionnelles de la médecine utilisées par le médecin pratiquant la saignée et le dosage régulier de composés au mercure nécessaires pour être remplacés par quelque chose de nouveau et qui améliore. ‟ Quelle est l'origine du ‛charlatanisme dans le clergé′ et autres, si ce n′est le charlatanisme chez les médecins? ˮ il demanda au médecin indigné. ‟ Vos échecs ont poussé les gens à essayer des expériences. ˮ

Boyden soutenait le vote et les droits de propriété des femmes, moins d′heures pour les travailleurs à l'usine, l'aide contre la faim en Irlande, les bibliothèques publiques, la réforme des prisons, et le bon traitement des animaux. Il s'opposa à la peine capitale. Il admirait son voisin de croisade au nord, Adin Ballou, chef de la communauté utopique à Hopedale, dans le Massachusetts. Les deux ont échangé des services ministériels et Boyden assista souvent aux conférences de Ballou et aux événements communautaires Hopedale. Ayant assisté à la nouvelle maison de réunion dédiée à Hopedale en 1860, Boyden loua la communauté pour ‟ chercher à réaliser l'annonce angélique de la paix sur la terre et la bonne volonté des hommes. ˮ

Pendant tout son pastorat à Woonsocket Boyden était l'officier en chef de la Rhode Island Universalist State Convention, de 1840 à 1861, et, après que la convention a été réorganisée, président, de 1861 à 1869. Il offrait le sermon annuel à la United States Universalist General Convention tenu à Baltimore en 1844. Outre un certain nombre de tracts, Boyden publia un livre de cantiques de l′école du dimanche, The Harp Eastern, 1848. Lui et sa congrégation présentèrent les célébrations publiques de Noël à Woonsocket dans les années 1850.

Boyden épousa Sarah Church Jacobs en 1831. Ils eurent un fils, John Richmond Boyden, qui est mort dans l'âge adulte. Aux prises avec une mauvaise santé chronique, Boyden prit un congé pendant plusieurs mois en 1857. Voyageant dans le New Hampshire les Boydens visitèrent une communauté Shaker et ont été impressionnés par ‟ une sérénité des visages qui indique la paix de Dieu dans l'âme. ˮ Ils ne dormaient pas dans la communauté, cependant, car il y avait des hébergements séparés pour les femmes et les hommes: ‟ n′étant pas préparés, même pour un divorce temporaire, [nous] avons demandé et obtenus un lieux très confortable avec une famille privée à proximité. ˮ

Après que Boyden est mort l'église universaliste, qu'il avait si longtemps servie, a tenu des services annuels à sa tombe. Ces commémorations régulières persistèrent dans le début du 20e siècle.

Le biographe de Hosea Ballou, Oscar Safford, mit Boyden avec Hosea Ballou 2d, Thomas Whittemore, et Lucius Paige dans un chapitre intitulé ‟ fils spirituels ˮ. ‟ Nous ne savons pas qui, dans sa génération le surpassait en grandeur de l'amour, l'amour chrétien qui reconnaît l'infini dans le fini, le Divin dans l'humain, et ressent la joie et la douleur d'un autre que lui-même ˮ, Safford a écrit. ‟ Aucun nom parmi ceux qui sont détenus en l'honneur de l'Église universaliste est considéré avec plus d'affection que John Boyden, le pasteur chrétien, qui avait le génie de l'amour. ˮ

*Un journal et d'autres documents relatifs à John Boyden sont dans les archives de la première église universaliste de Woonsocket, Rhode Island. Les archives comprennent des histoires dactylographiées de l'église et une transcription de "The 1847 Diary of Rev. John Boyden ˮ avec une introduction biographique de Peter Hughes et une collection transcrite y compris de nombreux articles de Boyden, "The First Universalist Church dans le Woonsocket Patriot , 1837- 1869. ‟ Publications Boyden pas déjà mentionnés comprennent Examen du Sermon du révérend M. Hill ‟ American Universalisme ˮ (1844), Examen d'un traité intitulé ‟ A Strange Thing ˮ (1845), (avec A. Abbott) bigoterie religieuse (1845), et ‟ Le Règne du Christ ˮ dans Le Helper Christian (1858). D'autres sources d'informations utiles et primaires sont les dossiers du gouvernement de Rhode Island, à la State House à Providence, Rhode Island et les questions du registre universaliste (1841-70). Il y a une notice nécrologique dans le numéro 1870. Oscard F. Safford inclus plusieurs pages sur Boyden dans Osée Ballou: A Marvellous Vie-Story (1889). Boyden est également mentionné dans Erastus Richardson, Histoire de Woonsocket (1876) et Charles Stickney, Savoir-Nothingism dans le Rhode Island (1894). Voir aussi John G. Adams, Cinquante ans notables (1883) et Peter Hughes, ‟ charlatanisme entre le Clergé: Médecine et ministère dans les conflits en 1848, ˮ Actes de la Unitarian Universalist Historical Society (1995).

Article le 2 août 2014 par Charles A. Howe and Peter Hughes

the Dictionary of Unitarian and Universalist Biography, an on-line resource of the Unitarian Universalist History & Heritage Society. http://uudb.orgtraduit de l'anglais au français par DidierLe Roux

Retour page d'accueil

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Le Roux Didier- Unitariens - © Depuis 2006 - Tous droits réservés

"Aucune reproduction, même partielle, autres que celles prévues à l'article L 122-5 du code de la propriété intellectuelle, ne peut être faite de ce site sans l'autorisation expresse de l'auteur ".

votre commentaire

votre commentaire

-

Herman Bisbee

Herman Bisbee ( October 29, 1833-July 6, 1879) is best known as the only American Universalist minister to have been found guilty of heresy. After losing his Universalist fellowship, he became a Unitarian.

Herman Bisbee ( October 29, 1833-July 6, 1879) is best known as the only American Universalist minister to have been found guilty of heresy. After losing his Universalist fellowship, he became a Unitarian. Herman was one of eight children of a Universalist farming family in West Derby (now Newport), Vermont. In 1853 he married Mary Phelps Sias, daughter of another Universalist family. After a brief period as a farmer, Bisbee moved with his wife and family to Canton, New York, where he enrolled in the recently established Theological School of St. Lawrence University. While a student, he preached to a congregation in Malone, New York. He was ordained there in 1864, the year of his graduation.

In 1865 Bisbee and his family moved to St. Paul, Minnesota, where he helped to organize a new Universalist congregation and served as its first minister. In 1866 he accepted a call to the Universalist church in nearby St. Anthony (later part of Minneapolis), following the death of its minister, Seth Barnes. In his Memoir of Rev. Seth Barnes, 1868, Bisbee praised his predecessor as a pioneer of Universalism in the West and a faithful disciple of "the living, loving, lowly Jesus."

Up till this time Bisbee had been a theologically traditional Universalist. Ebenezer Fisher, president of the Canton school, had approved of his views concerning the Bible and revelation. In 1868-69, however, he spent ten months as minister of the Universalist church in Quincy, Massachusetts. While there he became interested in the Transcendentalist and Natural Religion ideas of the previous generation of Unitarians—Ralph Waldo Emerson, Theodore Parker, James Freeman Clarke—and the radical new Free Religious movement. In 1869 he returned to Minnesota with a new message to preach.

In 1871 William Denton, a member of the Free Religious Association, lectured in Minneapolis on Charles Darwin's theory of evolution. James Harvey Tuttle, minister of the Minneapolis Universalist Church, responded with a sermons and lectures upholding a literal interpretation of the Bible. Bisbee and fellow Universalist minister William Haskell countered (and sometimes mocked) Tuttle's view in a series of lectures which became known as the "Minneapolis Radical Lectures." Bisbee's "Radical Lectures" included talks on miracles, on the origin of the Bible, and on natural religion, notably one called "The Important and Enduring in Religion," modeled on Theodore Parker's "Transient and Permanent in Christianity."

Reaction to Bisbee's lectures from his fellow Universalists was for the most part negative. An editorial in a leading Boston-based denominational newspaper, The Universalist, said that, since he denigrated the Bible and Christianity, he had no right to call himself a Universalist. Bisbee admitted that he had "pushed into prominence a different class of ideas from those which are generally pushed in Universalist Churches," but argued that he was only "defend[ing] the traditional liberality of the denomination" against "the extreme conservative tendencies developed by some leaders in the order."

Bisbee's challenge to traditional theology came at a crucial time in Universalist history. In 1870, the Universalist General Convention had voted to reaffirm the Winchester Profession of 1803, but without including the "liberty clause" which had permitted theological differences. Thus, for the first time, the Universalists had a prescribed creed against which individual Universalists' beliefs could be judged. Bisbee claimed that the Winchester Profession "was designed to cover great varieties of opinion," and that his beliefs were within the range of acceptable interpretations. He denied that any newspaper editor had the right to pass judgment on his beliefs, and challenged the denomination to bring him up on disciplinary charges. He was confident that if this was done he would be vindicated.

Early in 1872, the Committee on Fellowship, Ordination, and Discipline of the Minnesota Universalist Convention took Bisbee at his word and demanded that he surrender his letter of fellowship. At the state convention in June, he was formally charged with two counts of "unministerial conduct": for preaching heretical doctrines and for unbrotherly conduct toward James Tuttle. After a long debate, the convention passed a resolution withdrawing fellowship from him. In protest, Bisbee's fellow "radical," William Haskell, withdrew from the Minnesota Convention and united with the Illinois Convention. The editor of The Universalist, certainly no admirer of Bisbee's views, expressed dismay: "We must say that our Minnesota brethren have done a very extraordinary thing—one which the General Convention in Cincinnati should promptly and effectively correct."

Bisbee filed an appeal to the General Convention, where a Board of Appeal upheld the action of the Minnesota convention. The Board conceded that Bisbee had "expressed assent to the Winchester Profession" as required, but ruled that this "is not, in cases of doubt, to be regarded as conclusive evidence that either that he believes it, or preaches in accordance with it." Faced with the old problem of trying to prosecute heresy without defining orthodoxy, the Board noted, "It appears to be almost self-evident that the Universalist Church does know what its religious faith is" although "it may not be necessary or profitable for the denomination to state with any great particularity."

Bisbee's St. Anthony congregation, which had given him a unanimous vote of support, changed its name to the "First Independent Universalist Society" and prepared to leave the denomination with its minister. Within a few months, however, Bisbee resigned his ministry on the grounds of ill health, and moved to Boston.

Bisbee studied briefly at Harvard Divinity School in 1873 and then went abroad. In 1873-74 he studied at Heidelberg University. His first wife having died in 1872, in Heidelberg he married Clara Maria Babcock, daughter of Unitarian minister William Babcock. Clara had studied at Harvard Divinity School and served as assistant to her father. Together Clara and Herman served the Stepney Church in London's East End for a few months in 1874. On their return to America, Herman became minister of Hawes Place Unitarian Church in Boston, where he served until his death. Clara Bisbee lived until 1927. In 1881 she established the Boston Society for Ethical Culture, also known as the Free Religious Society, at Lyceum Hall in Boston.

Bisbee is largely remembered for forcing the Universalist denomination to face up to the issue of freedom of belief. After much debate and soul searching, in 1899 the General Convention adopted a new statement of belief, commonly referred to as the Boston Declaration. It identified "the five essential principles of Universalism: The Universal Fatherhood of God; the spiritual authority and leadership of his Son, Jesus Christ; the trustworthiness of the Bible as containing a revelation from God; the certainty of just retribution for sin; and the final harmony of all souls with God." The Winchester Profession was commended as containing these principles, and most importantly, the "liberty clause" was reinstated.

Most of what is known of Bisbee derives from Mary F. Bogue, "The Minneapolis Radical Lectures and the Excommunication of the Reverend Herman Bisbee," Journal of the Universalist Historical Society (1967-68). This contains substantial exceerpts from the primary documents. She did her research in what is now the Universalist Special Collection at the Andover-Harvard Theological Library in Cambridge, Massachusetts (formerly the collection was held at Tufts University), at the Church of the Redeemer in Minneapolis, Minnesota, and at the Minnesota Historical Society. Bisbee's story is also told in Russell Miller, The Larger Hope, vol. 2 (1985) and in Ernest Cassara, Universalism in America (1971). See also William Sasso, "American Universalism: 210 Years" and John Addington, "A Brief History: First Universalist Church of Minneapolis."

Article by Charles A. Howe - posted November 25, 2007All material copyright Unitarian Universalist History & Heritage Society (UUHHS) 1999-2016

Main Page | About the Project | Contact Us | Fair Use PolicyPolicy  votre commentaire

votre commentaire

-