-

Par unitarien le 19 Juin 2016 à 10:14

Edwin Chapin

Edwin Hubbell Chapin (December 29, 1814-December 26, 1880), Universalist minister, author, lecturer, and social reformer, was one of the most popular speakers in America from the 1840s until his death. He was revered for his eloquent tongue and passionate pleas for tolerance and justice.

Edwin was born in Union Village, New York, to Beulah Hubbell and Alpheus Chapin. The Hubbells and the Chapins had emigrated from England in the mid-1600s and settled in Massachusetts and Connecticut. Their descendants included doctors, soldiers, politicians, and clergy. A non-puritanical Calvinist, Edwin's father played the violin, was a great conversationalist, and made his living as an itinerant portrait painter. His mother was a cultured woman from Bennington, Vermont. Because the family moved often, schooling was intermittent for Edwin and his two younger sisters, Ellen and Martha. Their parents, however, instilled in them a love for books. When Edwin was 11, the family settled for a while in the West End of Boston. Instead of attending school, he worked as an errand boy and wrote poems to amuse his friends. At 13 he joined a neighborhood drama club, where he recited poetry, sang songs, and played comic roles with relish.

His pious parents, fearing that Edwin would choose an acting career, enrolled him in Bennington Seminary in Bennington, Vermont, a boys' academy noted for academic discipline. During his four years under the guidance of the gifted headmaster, James Ballard, Edwin blossomed into a witty, inspiring orator and poet. Although he could move an audience of townsfolk and fellow students to laughter and tears, no one predicted he would become a minister. After his graduation, he worked as clerk in the Bennington post office. As his employer and landlord was a lawyer, he began to think that he might want to pursue law as a career.

Chapin served eight months in two law offices in Troy, New York. While there, he enjoyed a brief stint as a political orator for Presidential candidate Martin Van Buren but disliked everyday legal drudgery. At the same time he was caught up in a religious revival. A Calvinist minister, thinking his ideas unsound, rebuffed his tentative application for advice about entering the ministry.

Depressed and discouraged, Chapin moved back with his family, who were then in Bridgewater, in central New York. From there he accompanied his father to nearby Utica. They lodged near the office of the Evangelical Magazine and Gospel Advocate, a Universalist magazine. Wandering into its store one day, he was intrigued by the ideas in the books on display of a God of love rather than fear, so different from the deity of his Calvinist upbringing. After he began to work in a law office across the street, he continued to frequent the store. He met and talked with the magazine's editor, Aaron Grosh, and with various Universalist clergymen, including Dolphus Skinner. He wrote poems, hymns and editorials for the Magazine and Advocate and was soon hired by the paper. He served as assistant editor, 1837-38. Converted by his exposure to the Universalist faith, and with Grosh's encouragement, he revived his desire to be a minister. In 1838 he delivered his first sermon in Litchfield, New York.

Although he had no college education or theological training, and only a year's exposure to Universalism, in 1838 Chapin was called to be pastor of the Independent Christian Church, in Richmond, Virginia, composed of both Universalists and Unitarians. Audiences flocked to hear the sermons and lectures of the young man with the powerful voice and magnetic personality. His tract, Universalism: What It Is Not, and What It Is, 1838, became widely popular. Universalism, he wrote, was not atheism, skepticism, or deism. Instead, "it teaches that all mankind will finally be saved from sin and its consequent misery." Universalists did not "argue against punishment,—against future punishment,—but against the endless duration of sin and misery." The same year, Chapin was ordained by the New York Central Association and married Hannah Newland of Utica, whom he had met at the Magazine and Advocate bookstore. She was his devoted companion for 42 years.

In 1839, on his way to the General Convention of Universalists, held in Portland, Maine, Chapin stopped in Charlestown, Massachusetts to attend the funeral of the minister Thomas F. King, father of Thomas Starr King. Having heard of Chapin's eloquence, the church leaders invited him to speak that evening. Soon he received a call to fill the now-vacant pulpit. His acceptance was delayed for a year, while he searched for a replacement in Richmond. Before he accepted, he wrote the congregation a letter confessing that he could not find scriptural proof for the doctrine of universal salvation, although he believed it to be in the "spirit of Christ." Also, he rejected the "doctrine of the trinity, of vicarious sacrifice to appease the wrath of God, of total depravity, original sin, etc. etc." He made it clear that he was an independent thinker who served "God and humanity"and preached not a creed but "Liberal Christianity." In spite of these reservations, he was enthusiatically welcomed by the congregation. Hosea Ballou, Hosea Ballou 2d, Thomas Whittemore, Otis A. Skinner, Sebastian Streeter, and Elbridge G. Brooks took part in his installation. He served the Charlestown church, 1840-45.

In Charlestown Chapin began to espouse the temperance, abolition, and anti-capital punishment causes of Theodore Parker, Horace Mann, William Lloyd Garrison, Charles Spear, and others. He was mentor and friend to Starr King, who "enjoyed a rich conversation with Bro. Chapin on philosophy and religion." Out of the grief following the death of his first born child, Edward Channing Chapin (named for William Ellery Channing), he wrote the book The Crown of Thorns: A Token for the Sorrowing, 1847.

Chapin alternated between a frenzy of productive activities—installations, ordinations, college commencements, speaking in favor of social reforms, sermons, publications, service as chaplain of the Massachusetts legislature and as a member of the State Board of Education—and exhausted depression. His generous contributions to charity, support of his father, and his purchases of rare books often outran his income. Partly in order to increase his income, in late 1845 he became the colleague of the aging Hosea Ballou at the Second Universalist Church in Boston. Here his advocacy of reforms, notably temperance, alienated some conservative Universalists, who, under Ballou, had not been used to such preaching. He moved on after only two years.

In 1848 Chapin was installed at the Fourth Universalist Society in New York City, where he remained for 32 years, preaching broad church Christianity and becoming the most popular preacher in the city. In 1852, when his congregation bought a larger church on Broadway, over 2,000 people came to the first Sunday evening service and hundreds were turned away. In 1866 the Fourth Universalist Society moved to a new building at 5th Avenue and 45th Street, The Church of the Divine Paternity.

Chapin's preaching was described as hypnotic. He was for a quarter-century the star of the Lyceum circuit, devoting half his time to traveling from Maine to Illinois to deliver his lectures. These addresses, on subjects such as "Orders of Nobility," "Modern Chivalry," "Social Forces," "Man and His Work," "Woman and Her Work," and "The Progress of Popular Liberty," were more intellectual and polished, if a little less emotional than his sermons. When Starr King was on a program with him, he always asked to speak before Chapin did. Chapin's fame was international. One of his most impassioned speeches was delivered to 3,000 people of different nationalities and languages at the 1850 Peace Congress at Frankfurt am Main. Even those who knew no English burst into applause, sensing the heartfelt eloquence.

Although seldom controversial in his sermons, Chapin was adamantly opposed to slavery. Despite his abhorrence of war and loss of life, he supported the Union side during the Civil War, which caused dissension in his church. Merchants in the congregation who had done business with Southern slave-holders objected to his public stance. In response to one attack, he told the members of the congregation that "While you have absolute control of your temple, you have no authority over my conscience."

Chapin appealed to a broad audience which included people from many faiths. He was not interested in theological differences, but in commonalities and in the spiritual aspects of religion. He rejected a literal reading of the Bible. It was a book, he said, "where each his dogma seeks, and each his dogma finds." He commended the moral principles set forth by Jesus Christ as the best path to salvation. He opposed his church adopting the sectarian Winchester Profession of Faith. Like the Restorationists, he believed that punishment of a limited duration might be required in the afterlife. Some complained that there was nothing especially Universalist in his sermons. He nevertheless rejected eternal damnation, believing that each person would eventually be saved by a loving God.

Chapin was enthralled by the scientific discoveries of his day. He could see no conflict between religion and science. "The more we learn of nature," he said, "the more clearly is revealed to us this fact—that we know less than we thought we did . . . as science, as nature, opens upon us, we find mystery after mystery, and the demand upon the human soul is for faith, faith in high, yea, in spiritual realities." "Faith is not the surrendering of our minds to that which is irrational and inconsistent," however. "In that which conflicts with our reason we cannot have faith." He thought that the faith we must have is "in realities that are not of time or sense."

Chapin preached continually on the obligation to care for all people, stressing their innate worth. In 1869 his congregation raised funds to establish, in his honor, the Chapin Home for the Aged and Infirm in New York City, open to anyone over 65. His wife was its first and long-time president. Bringing comfort and cheer to its residents was a favorite pastime for Chapin.

In his book Humanity in the City, 1854, Chapin observed, "There sits the beggar, sick and pinched with cold; and there goes a man of no better flesh and blood, and no more authentic charter of soul, wrapped in comfort, and actually bloated with luxury." This teaches us, he reflected, "our duty and our responsibility in lessening social inequality and need." Large cities heighten both good and evil, he wrote in Moral Aspects of City Life, 1853: "The close contact that excites the worst passions of humanity also elicits its sympathies—and noble charities are born of all this misery and guilt." He believed his major role in life was to help alleviate this misery. "The preacher, especially in the city," he said, "must be a true reformer, definite, emphatic, bold." Although he criticized institutions, denounced manifest evils, and worked endlessly for social causes, he did not denounce individuals, believing moral persuasion more effective in changing behaviors and lives.

Chapin's library of nearly 10,000 volumes included poetry, plays, folk-lore, legends, ballads, biographies, history, philosophy, progressive social thought, essays, orations, and practical Christianity, but little theology or Biblical criticism. He rarely used quotations or allusions in his talks. Instead, he used his reading to understand the great issues of life and faith.

At ease behind a podium, Chapin was shy and uncomfortable in social settings. He preferred the company of family and close friends (such as P. T. Barnum), where he was relaxed, witty, and jovial. He rarely visited parishioners, except the sick or grieving. He disliked small talk, and quickly disappeared after services and lectures to avoid meeting strangers and autograph seekers. Fortunately, his wife Hannah was even-tempered, cheerful, sociable, and a skilled manager of her husband's business affairs.

In 1856 Chapin was given a Doctor of Divinity degree by Harvard College. He received an LL.D. from Tufts College in 1878. He was a trustee of Bellevue Medical College and Hospital and a member of the State Historical Society, the beneficent society called Order of Odd Fellows, and the prestigious Century Club, composed of "authors, artists, and amateurs of letters and the fine arts."

Chapin preached his last sermon on Palm Sunday, 1880. His health had deteriorated for six years from progressive muscular atrophy, but he refused an assistant and resisted retirement until forced by debilitation. After a brief trip to Europe and a summer relaxing at the family cottage in Pigeon Cove, Cape Ann, Massachusetts, he steadily grew worse and died a few days before his 66th birthday.

The funeral service was conducted by James M. Pullman of the Church of Our Saviour (Sixth Universalist Society in New York City). The sermon was preached by his good friend, the Congregationalist minister Henry Ward Beecher, who said later: "The audience at Chapin's funeral was remarkable. It came the nearest being a representation of the Church Universal I ever saw . . . Not another minister in New York could draw such a diversity of people to his burial." Other participants included Henry Whitney Bellows of the Church of All Souls, President Elmer H. Capen of Tufts College, Robert Collyer of the Unitarian Church of the Messiah, and Thomas Armitage of the 5th Avenue Baptist Church. Chapin was buried in Greenwood Cemetery. Seven months later Hannah died and was laid beside him. They were survived by three children.

Among Chapin's many books and tracts are Duties of Young Men (1840), The Positions and Duties of Liberal Christians (1842), The Philosophy of Reform (1843), Three Discourses on Capital Punishment (1843), The Relation of the Individual to the Republic (1844), Hymns of Christian Devotion (1846, with John G. Adams), True Patriotism (1847), The Fountain: A Temperance Gift (1847), Duties of Young Women (1848), Discourses on the Lord's Prayer (1850), Christianity, the Perfection of True Manliness (1854), The American Idea and What Grows Out of It (1854), A Discourse on Shameful Life (1859), A Discourse on the Evils of Gaming (1859), Living Words (1860), Providence and Life (1869), Lessons of Faith and Life (1877), The Church of the Living Word (1878), and The Church of the Living God (1881).

The only full-length biography of Chapin is Sumner Ellis, Life of Edwin H. Chapin (1882). There are biographical sketches in David Robinson, The Unitarians and the Universalists(1985) and Mark Harris, Historical Dictionary of Unitarian Universalism (2004). See also Russell Miller, The Larger Hope, vol. 1 (1979). Obituaries include The Sun (New York City, December 28, 1880), and the Universalist Register (1882).

Article by June Edwards - posted May 24, 2006All material copyright Unitarian Universalist History & Heritage Society (UUHHS) 1999-2016

votre commentaire

votre commentaire

-

Par unitarien le 5 Juin 2016 à 15:06

Orestes Brownson

Orestes Augustus Brownson (Sept. 16, 1803-April 17, 1876) as a maverick Universalist and Unitarian minister, then an independently-minded journalist, essayist, and critic, was a wide-ranging commentator on politics, religion, society, and literature with connections to the Transcendentalist movement. Disillusioned with liberal religion and radical politics, in 1844 he converted to Roman Catholicism and became a Catholic intellectual, a constitutional conservative, and a fierce critic of Protestantism.

Orestes Augustus Brownson (Sept. 16, 1803-April 17, 1876) as a maverick Universalist and Unitarian minister, then an independently-minded journalist, essayist, and critic, was a wide-ranging commentator on politics, religion, society, and literature with connections to the Transcendentalist movement. Disillusioned with liberal religion and radical politics, in 1844 he converted to Roman Catholicism and became a Catholic intellectual, a constitutional conservative, and a fierce critic of Protestantism.Orestes was born in the frontier village of Stockbridge, Vermont. He and his twin sister were the youngest children of Sylvester Brownson and his wife Relief Metcalf. In 1805 Sylvester died, leaving a destitute 28-year-old widow with five children. Orestes lived with his mother until he was six, old enough to remember her Universalist teaching about the "gift of a Saviour's love to sinners." He was then sent to live with an older couple in Royalton, Vermont. They were Congregationalists but did not attend church because they disapproved of the evangelical preaching in their local church. They instructed Orestes in the rudiments of the Reformed faith and encouraged him to explore the religious options Royalton had to offer. He did not unite with any church but had a rich spiritual life centered on private reading of the Bible.

When Orestes was 14, his family was reunited and moved to Ballston, New York, near Saratoga. Orestes was apprenticed to James Comstock, the owner, editor and printer of the Independent American newspaper, in the fashionable resort of Ballston Spa. Accustomed to the relative equality of a Vermont farming village, Orestes was shocked by the extravagance of the resort's guests and the servility of the slaves, servants, and staff who catered to them. "Wealth, more frequently the veriest shadow of wealth, no matter how got or how used, is the real god, the omnipotent Jove, of modern idolatry," he wrote bitterly. Brownson's work on the newspaper was the beginning of his political education. From Comstock, he absorbed the idea that democracy was threatened by money and privilege and that "nonproducers" such as lawyers, bankers, and the clergy were parasites living off the labor of the working class. These principles remained the basis of his politics throughout the 1820s and 1830s.

At the urging of his aunt, Asenath Delano, a leader of the small Universalist society in Ballston, Brownson read some basic Universalist literature. He was unimpressed by Elhanan Winchester, Charles Chauncy, and Joseph Huntington, and disturbed by Hosea Ballou's Treatise on Atonement. Ballou's ridicule of orthodox belief, together with the worldly and irreligious atmosphere of Ballston Spa, caused Brownson to wonder if there was any truth to religion at all. In an 1834 letter, he wrote that he "was soon a Deist, and before I was seventeen an Atheist." When he was 19, however, he made a desperate attempt to regain his faith by joining the Presbyterian church. The experience was an unhappy one, and he left the church after nine months.

By this time Brownson's apprenticeship had ended. He studied for a few months at Ballston Academy, then became a schoolteacher in nearby Stillwater and in Camillus, in western New York. In 1824 he took a teaching position in Springwells, Michigan, near Detroit. Within a few months, he contracted malaria, and spent most of his time in Michigan ill or convalescing. In less than a year he was back in Camillus. His brief stay in Michigan may nevertheless have changed the course of his life. Detroit at that time was a largely French-speaking, Catholic community. At a time when most Americans thought of Catholicism as, at best, an obsolete religion superseded by a more advanced form of Christianity, Brownson was one of the few American Protestants to have experienced the Catholic church as a living and benign presence.

During his time in Springwells and Camillus, Brownson continued to consider the arguments for and against universal salvation. In 1825 he declared himself a Universalist. He consulted Dolphus Skinner, the Universalist minister in Saratoga Springs, New York, about entering the ministry. Skinner recommended that he study with his own mentor, Samuel Loveland. Brownson was soon after accepted into fellowship as a Universalist evangelist. During 1825-26 he prepared for the ministry under Loveland's guidance. He was ordained in 1826.

Brownson spent the three and one-half years of his Universalist ministry at a succession of small churches in New York state. After his ordination, he obtained a temporary position supplying pulpits in Fort Ann and Whitehall, near the Vermont border. This was followed by a series of settlements in central New York: Litchfield, 1826-27; Ithaca and Genoa, 1827-28; and Auburn, 1829. In 1827 Brownson married Sally Healy, a daughter of the family with which he had boarded while teaching in Camillus. The couple eventually had eight children.

Shortly after arriving in New York, Brownson was caught up in a dispute about the advisability of organizing a New York State Convention of Universalists. He joined a group of ministers, led by Linus Smith Everett, who opposed the convention out of concern about its ill-defined and, in their opinion, arbitrary disciplinary powers. This drove a wedge between Brownson and Dolphus Skinner, who was one of the convention's strongest supporters.

When Everett moved to Massachusetts in late 1828, he arranged for Brownson to succeed him as minister at Auburn and as editor of a Universalist newspaper, theGospel Advocate. An inexperienced editor, Brownson soon became embroiled in a dispute with Theophilus Fisk, a former owner of the Gospel Advocate. In the course of the argument, Fisk charged that Brownson had renounced Christianity and become "a secret agent of infidelity."

Though Brownson's theology was less orthodox than Fisk's, it was well within the range of opinions held by Universalists of his time. Many Universalists, however, were prepared to believe Fisk's allegations - particularly after Brownson defended Abner Kneeland, then being dismissed from his church on the ground of infidelity, and wrote admiringly of the notorious freethinker Frances Wright. Even those who approved of Brownson's theology criticized the Gospel Advocatefor "splitting straws" with other Universalists instead of spreading the message of universal salvation. At a time when Universalists were worried by the rise of a confident and united evangelical party in American politics, they were particularly sensitive to anything that might bring the denomination into disrepute.

In October, 1829, Brownson returned from a six-week trip to New England to find that, in his absence, Dolphus Skinner had bought the Gospel Advocate. He merged it with his own Utica Magazine and eliminated Brownson's editorial position. Unable to stay on as assistant editor or to find work on other Universalist publications, Brownson joined the staff of the Free Enquirer, the avowedly anti-religious paper co-edited by Frances Wright. This confirmed the mistaken idea that his enemies already had about him: that he was an "infidel," and possibly mentally unbalanced as well. Brownson's separation from the Universalist denomination was made formal in September 1830, when the Universalist General Convention voted "that there is full proof that said Kneeland and Brownson have renounced their faith in the Christian Religion, which renunciation is a dissolution of fellowship with this body."

As the years went by, Brownson found it convenient to accept "infidelity" as the explanation for his departure from Universalism. As a Unitarian minister in the 1830s, he wore the "infidel" label with a certain degree of pride, using it to establish himself as an authority on the arguments most likely to appeal to unbelievers. His 1840 novel Charles Elwood, or the Infidel Converted was understood to be a thinly disguised history of his own case. After he converted to Catholicism, the story of his past infidelity fit in with the narrative of his progress toward Catholicism, and supported his case for the inadequacy and incoherence of Protestantism.

After his departure from the Universalists, Brownson renounced sectarian religion in favor of social reform, declaring himself to be a "philanthropist" rather than a "religionist." For a few months in 1830 he edited the Genesee Republican, a newspaper of the Workingmen's party in New York State, but he quickly decided that this party lacked the broad support necessary to spearhead an effective reform movement.

Just as he became disillusioned with Workingmen politics, Brownson experienced a spiritual conversion that led him to declare himself a Unitarian. Behind this re-conversion lay his belief that he detected a divine voice within his soul, an experience that reaffirmed for him the existence of a paternal God. By early 1831, Brownson had resumed preaching on an independent basis, affirming his affinity for Unitarians, who taught that "God is our Father, that all men are brethren, and that we should cultivate mutual good will." In making this turn towards Unitarianism, Brownson had been influenced by William Ellery Channing, especially his 1828 sermon, "Likeness to God."

Brownson established a newspaper called the Philanthropist, probably the only Unitarian periodical in New York State at the time. Although he managed to keep it afloat for about two years, he was forced to fold the insolvent paper in 1832. Financial necessity and growing ambitions led Brownson to seek a regular pulpit, with a salary to support himself, his wife, and two young sons. He accepted a call to Walpole, New Hampshire, a move that put him within the orbit of Boston, the center of American Unitarianism. He attended gatherings of the American Unitarian Association and began publishing essays in Boston Unitarian periodicals, including the Christian Register, the Unitarian, and the Christian Examiner.

In 1834 Brownson began serving the church in Canton, Massachusetts, fifteen miles from Boston. From that post, he began to advocate for fundamental social reform. In an 1834 Fourth of July address, for instance, Brownson expressed concern that economic inequality was growing, and noted that the nation was failing to live up to the principle of equality embedded in the Declaration of Independence. His social radicalism alienated some of his parishioners. When his contract was renewed in 1836, ten church members voted against his retention.

In the summer of 1836, Brownson seized upon an opportunity suggested by George Ripley, to become a minister-at-large for the poor and working classes of Boston (a position previously filled by Joseph Tuckerman). Moving his family to the suburb of Chelsea, Brownson launched the Society for Christian Union and Progress, which he hoped would allow him to unite Christianity with social reform. In 1836 he published a short book, New Views of Christianity, Society, and the Church, in which he diagnosed the ills of contemporary Christianity and proposed a cure based upon the theological principle of atonement. He reinterpreted atonement by envisioning Jesus mediating between the spiritual and the material; once humanity understood the unity of the spiritual and the material, he believed, "Man [will] stand erect before God as a child before its father," and therefore "Man will reverence man." Brownson achieved rapid success in attracting listeners—hundreds attended his weekly preaching.

The Panic of 1837 inspired Brownson to sharpen his criticisms of the economic status quo. In a fervid sermon entitled "Babylon is Falling," he predicted the end of the commercial system of banks and paper money, which he believed promoted "artificial inequality." William Ellery Channing and other socially conservative Unitarians were less than pleased with Brownson's radical pronouncements. Brownson, however, was energized by his time in Boston. In 1838 he launched theBoston Quarterly Review, in which he hoped to reach a larger audience.

The next several years were tumultuous for Brownson. In 1836, with a number of current and former Unitarian ministers, including his friend Ripley, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Frederic Hedge, and Theodore Parker, he had attended the first meeting of what would become known as the Transcendentalist Club. Brownson expressed support for the basic principle of Transcendentalism: that every human had the potential to gain direct, intuitive access to spiritual and moral truth. Though he harshly criticized the radical individualism expressed by Emerson in his 1838 address to the Harvard Divinity School graduates and by Parker in his 1841 sermon "The Transient and Permanent in Christianity," Brownson nevertheless aligned himself with the Transcendentalists during the late 1830s and early 1840s.

Brownson harnessed his evolving religious beliefs to his desire for radical social and economic change. He called first for a new church and then, more radically, for "no church," by which he meant the replacement of the morally hollow activities of praying and psalm-singing with strenuous effort to create an actual Christian community. He asserted that social reform is the true religion of Jesus: "No man can enter the kingdom of God, who does not labor with all zeal and diligence to establish the kingdom of God on the earth; who does not labor to bring down the high, and bring up the low; to break the fetters of the bound and set the captive free." In his incendiary 1840 essay "The Laboring Classes," he predicted possible class warfare—"now commences the new struggle between the operative and his employer, between wealth and labor"—and argued for a radical solution to the inequality generated by the wage system: the abolition of hereditary property and the creation of a fund to provide educational and occupational opportunities for all young men and women as they reached adulthood. The essay was greeted with intense hostility, even by his own Democratic party.

Brownson was disappointed by the response to his plan and devastated by the Whig victory in the presidential election of 1840. He believed that voters had been duped by the packaging of William Henry Harrison as the "man of the people" when the Whigs' policies actually supported the economic interests of the wealthy and undermined constitutional limitations on government power. Brownson was one of the few people at the time who understood the implications of the commodification of public opinion and the threat it posed to democratic government. Of what use was theoretical political equality if the wealthy could use their wealth to convince the working classes to vote against their own best interests? "Man, against man and money," he recognized, was "not an equal match."

As Brownson became disillusioned with democratic politics and secular reform in general, he experienced another resurgence of faith that led him to return to preaching in 1842. Later that year, he published an open letter to Channing entitled The Mediatorial Life of Jesus. He believed that Pierre Leroux's concept of the collective life of humanity explained the transmission of human sinfulness from generation to generation. He saw in this a means of redemption. Jesus, who was both divine and human, performed the critical function of transmitting his divine life to humanity. All that humanity needed to do to be saved was to join in communion with the divine essence of Jesus.

In early 1843 Brownson published an extraordinary series of articles in the Christian World, a new Unitarian periodical. After establishing a few key principles—that humans were sinful, that they needed to be redeemed, and that God had surely provided a means of redemption—Brownson began his intellectual march toward Rome. He explicitly repudiated traditional Protestant soteriology, denying that individuals could read the Bible profitably without guidance and arguing that faith was the result rather than the cause of being saved. What was needed, Brownson asserted, was a church that embodied Christ's "life" (in Leroux's sense) and that could provide both guidance and grace. TheChristian World cut Brownson off before he could draw conclusions about what church deserved allegiance, but his trajectory made it clear enough that he no longer represented a Unitarian perspective.

For Brownson, it remained but to answer a historical question: which church was the true church? Ideally, the fragments of the church universal might unite, but barring that unlikely outcome, Brownson was beginning to see that his line of thought led him almost inexorably toward the Roman Catholic Church. In the July 1844 issue of Brownson's Quarterly Review (he had revived his journal earlier that year), he announced his final conclusion: "either the church in communion with the See of Rome is the one holy catholic apostolic church or the one holy apostolic church does not exist."

After Brownson, along with his wife and children, converted to Catholicism, he became an aggressive Catholic apologist, whose anti-Protestant rhetoric alienated even some Catholics. By the late 1850s he had adopted a more conciliatory tone, emphasizing the continuity between Catholic and American values, and encouraging Catholic immigrants to take their rightful place as Americans. His autobiography, The Convert, 1857, was part of his effort to explain Catholicism to Protestant Americans. During the 1860s, his most liberal Catholic period, he argued that the Catholic church should incorporate insights from modern science and democracy.

Although Brownson disapproved of slavery, before the Civil War he had opposed the abolitionist movement. Since he believed that labor for wages was tantamount to slavery, he did not think slavery justified placing the nation at risk. Once secession and war had actually come, he supported the Union and supported emancipation as a war measure. He became a Republican and ran for Congress, unsuccessfully, in 1862. After losing two sons in the war, in 1864 Brownson ended the twenty-year run of his Quarterly Review.

After the war Brownson continued to write for other Catholic publications. He remained an active lecturer and a prolific writer until his death in 1876. Although he sometimes accepted oversight from his bishop, he never abandoned the spirit of intellectual freedom that he had developed as a Universalist and a Unitarian.

The Archives of the University of Notre Dame hold the Orestes A. Brownson Papers. Letters written by Brownson exist in numerous libraries, including the Houghton Library at Harvard University. For early correspondence, see Daniel Barnes, "An Edition of the Early Letters of Orestes Brownson" (Univ. of Kentucky thesis, 1970). The best resource for locating Brownson's published writings is Patrick W. Carey, Orestes A. Brownson: A Bibliography, 1826-1876 ( 1997). Most of Brownson's published work is available in one of three editions: The Early Works of Orestes A. Brownson, 7 vols, edited by Patrick W. Carey (2000-2005), which collects Brownson's writings up to 1844; The Works of Orestes A. Brownson, 20 vols, edited by Henry F. Brownson (1882-1906), which contains Brownson's post-Catholic conversion publications; and Orestes Brownson: Works in Political Philosophy, 5 volumes (projected), edited by Greg Butler (2003- ).

Brownson's autobiography, The Convert (1856), is an essential work, if used carefully and in the light of other sources. The best modern biography of Brownson is Patrick W. Carey,Orestes A. Brownson: American Religious Weathervane (2004). A number of older biographies, including Henry F. Brownson, Orestes A. Brown's Early Life (1898), Middle Life(1899), and Later Life (1900); Theodore Maynard, Orestes Brownson: Yankee, Radical, Catholic (1943); and Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., A Pilgrim's Progress: Orestes A. Brownson(1939) continue to be valuable resources. Brownson's earliest years are covered by Lynn Gordon Hughes, "The Making and Unmaking of an American Universalist: the Early Life of Orestes A. Brownson, 1803-1829" (Brown Univ. thesis, 2007). Part of this was published as "Orestes A. Brownson's This-Worldly Universalism," Journal of Unitarian Universalist History (2008). On Brownson's middle years, see David J. Voelker, "Orestes Brownson and the Search for Authority in Democratic America" (Univ. of North Carolina at Chapel Hill dissertation, 2003). Philip F. Gura takes Brownson's roles in the Unitarian and Transcendentalist movements seriously in American Transcendentalism: A History (2007). Ann C. Rose,Transcendentalism as a Social Movement, 1830-1850 (1981) and William R. Hutchison, The Transcendentalist Ministers: Church Reform in the New England Renaissance (1959) are also valuable studies on this count.

Article by Lynn Gordon Hughes and David Voelker - posted November 2, 2009All material copyright Unitarian Universalist History & Heritage Society (UUHHS) 1999-2016

votre commentaire

votre commentaire

-

Par unitarien le 29 Mai 2016 à 10:06

Olympia Brown

Olympia Brown (January 5, 1835-October 23, 1926) dedicated her life to opening doors for women. Among only a handful of women to graduate from college, she received her Bachelor of Arts degree from Antioch in 1860 and three years later became the first woman graduate of a regularly established theological school: St. Lawrence University. She was ordained a Universalist minister, the first woman to achieve full ministerial standing recognized by a denomination. As a young minister, she took an active role in the women's suffrage movement and was one of the few original suffragists who lived to vote in the 1920 presidential election.

Olympia Brown (January 5, 1835-October 23, 1926) dedicated her life to opening doors for women. Among only a handful of women to graduate from college, she received her Bachelor of Arts degree from Antioch in 1860 and three years later became the first woman graduate of a regularly established theological school: St. Lawrence University. She was ordained a Universalist minister, the first woman to achieve full ministerial standing recognized by a denomination. As a young minister, she took an active role in the women's suffrage movement and was one of the few original suffragists who lived to vote in the 1920 presidential election.The first of four children, Olympia Brown was born to Vermont Universalists Asa B. and Lephia Olympia Brown, pioneers in Prairie Ronde, Michigan. Determined to give his children a good education, her father built a schoolhouse on his farm. He and Olympia rode from house to house to enlist their neighbors' donations toward hiring a teacher. The Brown children later attended school in the nearby town of Schoolcraft. Olympia was determined to go to college and persuaded her father to allow her and a younger sister to enter Mary Lyons's Mount Holyoke Female Seminary in Massachusetts. After an unhappy year in the rigidly Calvinistic atmosphere there, Olympia went to Antioch College in Yellow Springs, Ohio, where Horace Mann was president. Her experience there was so positive that her family moved to Yellow Springs for all four children to get a good education.

While at Antioch, Olympia Brown invited Antoinette Brown (no relation) to lecture and preach. "It was the first time I had heard a woman preach," she remembered, "and the sense of victory lifted me up. I felt as though the Kingdom of Heaven were at hand." Her next step was theological school, even though theological schools at that time did not welcome women.

"The ministry was the first objective of her life," wrote Gwendolen Brown Willis, "since in her youthful enthusiasm she believed that freedom of religious thought and a liberal church would supply the groundwork for all other freedoms. Her difficulties and disillusionments in this field were numerous. That she could rise superior to such difficulties and disillusionments was the consequence of the hopefulness and courage with which she was richly endowed."

The Unitarian School of Meadville, Pennsylvania, replied to her request for admission saying that "the trustees thought it would be too great an experiment" to admit a woman. Oberlin replied that she could be admitted but could not participate in public exercises. Finally, Ebenezer Fisher, President of the Universalist Divinity School at St. Lawrence University, offered her admission but added that he "did not think women were called to the ministry. But I leave that between you and the Great Head of the Church." This, Olympia thought, "was exactly where it should be left. But when I arrived, I was told I had not been expected and that Mr. Fisher had said I would not come as he had written so discouragingly to me. I had supposed his discouragement was my encouragement."

Entering divinity school in 1861, she completed her course of study in 1863. She had to convince those opposed to women in the ministry that they could complete the required course of study as commendably as she had. Then she had to convince the reluctant ministers to ordain her and allow her to be called to the parish ministry. Despite considerable opposition, Brown prevailed in both goals. This determination characterized her throughout her long and fruitful life.

In 1864 she was called to her first full-time parish ministry in Weymouth Landing, Massachusetts. At this time Olympia Brown became active in the women's rights movement, working with Susan B. Anthony, Lucy Stone and other leaders. In the summer of 1867, at the urging of Lucy Stone and her husband, Henry Blackwell, she agreed to take on a rigorous campaign in Kansas to urge passage of a woman suffrage amendment. The Weymouth Landing parish generously gave their minister a four-month leave of absence to fulfill this commitment.

Although Henry Blackwell assured Brown that he had made all the arrangements for her campaign, she arrived in Kansas to find that little if anything had been done in her behalf. She would have to make her own travel arrangements, find lodgings in each town, advertise her speaking engagements, secure halls in which to speak and deal with those determined to disrupt her speeches. Often she had to face down hostile townspeople who wanted to discredit her and the cause of woman suffrage. Brown took such obstacles as challenges to be surmounted and kept her eyes firmly on her goal. In spite of unbearable heat and brutal winds, she persevered and mounted a spirited campaign, delivering more than 300 speeches. She was not discouraged when only one-third of the voting population (all male, of course) approved the amendment. In spite of the final vote Susan B. Anthony considered Olympia Brown's work a glorious triumph.

By 1870 Brown was ready for another challenge and accepted a call to the Universalist Church in Bridgeport, Connecticut, "thinking it a larger field of usefulness." Even though the church had many members, "some had lost interest and there had even been an inclination to close the church." She also found that "unlike my Weymouth people, they had no such breadth of vision."

Although her mother and her friends advised her against marriage because they thought it would interfere with her career as a minister, she married John Henry Willis in 1873. She "thought that with a husband so entirely in sympathy with my work, marriage could not interfere, but rather assist. And so it proved, for I could have married no better man. He shared in all my undertakings." As did Lucy Stone, Olympia Brown kept her maiden name, with Willis's agreement. It was a most felicitous marriage. When her husband died, unexpectedly in 1893, she wrote: "Endless sorrow has fallen upon my heart. He was one of the truest and best men that ever lived, firm in his religious convictions, loyal to every right principle, strictly honest and upright in his life,....with an absolute sincerity of character such as I have never seen in any other person." A son, Henry Parker Willis, was born in 1874 and a daughter, Gwendolen Brown Willis, in 1876.

During her maternity leave for her first child, a faction at the Bridgeport church started agitating to terminate her ministry. As she writes in her autobiography: "although (or because) my parish gave me a vote of endorsement passed by a large majority, these enemies continued....calling in ministers from neighboring churches...promulgating the doctrine, 'what you need here is a good man.'"

At the end of 1874, Brown decided to resign her ministry. She and her husband stayed in Bridgeport for two more years, during which time her daughter was born. With characteristic spirit, Olympia recounts "after this tempestuous time at Bridgeport, I considered where I should go to continue the work of preaching, to which I had, as I thought, a distinct calling."

Discovering that a Universalist church in Racine, Wisconsin, was in need of a minister, she wrote to Mr. A. C. Fish, the clerk of the society, to offer her services. He wrote back that the parish was in an unfortunate condition, thanks to "a series of pastors easy-going, unpractical and some even spiritually unworthy, who had left the church adrift, in debt, hopeless and doubtful whether any pastor could again rouse them." This was precisely the kind of challenge that Olympia welcomed. It is also true that her options were limited.

Of her career as a parish minister she writes: "Those who may read this will think it strange that I could only find a field in run-down or comatose churches, but they must remember that the pulpits of all the prosperous churches were already occupied by men, and were looked forward to as the goal of all the young men coming into the ministry with whom I, at first the only woman preacher in the denomination, had to compete. All I could do was to take some place that had been abandoned by others and make something of it, and this I was only too glad to do."

With two small children to support, John Willis closed his business in Bridgeport and went ahead to Racine to find a house and employment. This type of support for his wife's endeavors was typical of him throughout their married life. He became one of the owners of The Racine Times-Call newspaper and worked actively to support his wife's ministry.

Rejuvenating the Universalist society in Racine was not a task for the faint of heart, but Brown set about it with her usual competence, dedication and practical skill. Not only did she breathe new life into the society, but she also established it as a center of learning and cultural activities. Bringing famous speakers like Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Julia Ward Howe, and Susan B. Anthony, she added immeasurably to the life of the surrounding community.

After nine years of rebuilding, she felt that her parish was able to sustain itself, and she made a momentous decision. At the age of 53 she decided to make a career change. Though she would continue to work as a part-time minister in smaller Wisconsin congregations, Brown left full-time ministry to become an activist for women's rights. Because her new role necessitated a great deal of travel, she was fortunate to have both a supportive husband and a capable mother at home to help care for the family.

Olympia Brown was a tireless and effective organizer for suffrage initiatives at the state and national level, leading the Wisconsin Suffrage Association for many years and serving as Vice-president of the National Woman Suffrage Association, Like Matilda Joslyn Gage and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, she promoted a broad range of reforms aimed at women, Believing that education was the key to women's advancement, she worked tirelessly to have women admitted to colleges and professional schools.

By the 1890s Brown was convinced that the suffrage movement was languishing under what she considered the lackluster leadership of Carrie Chapman Catt and Anna Howard Shaw. Little progress was being made toward a suffrage amendment, the older suffragists had either died or were being ignored, and in her opinion the fire seemed to have gone out of the movement. Not until Alice Paul and Lucy Barnes started the Woman's Party in 1913 did Brown feel optimistic about the suffrage cause. She welcomed the more confrontational and street-wise tactics of the Woman's Party and was elated with their strategy of mounting large vigils and demonstrations to mobilize support. When she was asked to be a charter member of this more militant and energetic group, she stated "I belonged to this party before I was born."

Brown joined in many of the demonstrations organized by the Woman's Party. In freezing rain, in bitter cold, in spite of dangerous confrontations and little police protection from hecklers, the octogenarian minister from Wisconsin was there. During one memorable demonstration, protesting Woodrow Wilson's turning his back on the suffrage amendment, she publicly burned his speeches in front of the White House. When the suffrage amendment was finally passed in 1919, Brown was one of the few original suffragists who was still alive to savor the triumph. She voted in her first presidential election at the age of 85.

Speaking in the Racine church in the fall of 1920 on the changes that had taken place since her resignation as minister, she said, "the grandest thing has been the lifting up of the gates and the opening of the doors to the women of America, giving liberty to twenty-seven million women, thus opening to them a new and larger life and a higher ideal."

In this sermon, she also testified to the importance in her life of Universalism, "the faith in which we have lived, for which we have worked, and which has bound us together as a church. . . . Dear Friends, stand by this faith. Work for it and sacrifice for it. There is nothing in all the world so important to you as to be loyal to this faith which has placed before you the loftiest ideal, which has comforted you in sorrow, strengthened you for the noble duty and made the world beautiful for you."

After the suffrage victory, Brown dedicated herself to promoting world peace and became one of the original members of the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom.

In her later years she spent summers at her lakeside home in Racine and winters in Baltimore with her daughter Gwendolen, who taught Greek and Latin at the Bryn Mawr School there. She died in Baltimore at 91 and was buried beside her husband in Racine's Mound Cemetery.

At the time of her death, The Baltimore Sun captured the independence, fearlessness and passionate commitment to justice of the Reverend Olympia Brown by stating; "Perhaps no phase of her life better exemplified her vitality and intellectual independence than the mental discomfort she succeeded in arousing, between her eightieth and ninetieth birthdays, among the conservatively minded Baltimorans."

The church Brown helped to vitalize in Racine has been re-named the Olympia Brown Unitarian Universalist Church. In 1975 a group of parishioners mounted a successful campaign to have an elementary school in Racine named in her honor. Nothing would have made this proponent of education, especially for women, prouder.

To honor the centennial of her ordination in 1963, the Theological School at St. Lawrence University unveiled a plaque which reads in part:

Preacher of Universalism

Pioneer and Champion of Women's Citizenship Rights

Forerunner of the New Era

The flame of her spirit still burns today.

Olympia Brown's papers and documents relating to her work are held at the Schlesinger Library, the Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts; the State Historical Society of Wisconsin; and in the papers of the National Woman's Party at the Library of Congress. Brown's writings include "Hand of Fellowship" and "Installation Sermon," Services for the Ordination of the Reverend Phebe A. Hanaford as Pastor of the First Universalist Church in Hingham, Massachusetts, Feb. 19, 1868 (1870); "The Higher Education of Women," The Ladies' Repository, A Universalist Monthly Magazine for the Home Circle (1874); "Crime, Capital Punishment and Intemperance," Papers and Addresses, Columbian Congress of the Universalist Church, Chicago (1893); Acquaintances Old and New Among Reformers (1911); and Democratic Ideals; A Memorial Sketch of Clara B. Colby(1917). Some of Browns works are collected in Dana Greene, editor, Suffrage and Religious Principle: Speeches and Writings of Olympia Brown (1988). "Olympia Brown: Two Sermons: 'But to Us There is One God' and 'Man Does not Live by Bread Alone,'" with an introduction by Ralph N. Schmidt, was published in The Annual Journal of the Universalist Historical Society (1963). Printed in the same issue was "Olympia Brown: An Autobiography," edited and compiled by Gwendolyn Brown Willis. Most of the quotations in the above article come from this source.There is a full-length biography: Charlotte Cote, Olympia Brown: The Battle for Equality (1988). Other biographical studies of Brown include Charles E. Neu, "Olympia Brown and the Woman's Suffrage Movement," Wisconsin Magazine of History (Summer, 1960); Nancy Gale Isenberg, "Victory for Truth: The Feminist Ministry of Olympia Brown," a master's thesis for the University of Wisconsin at Madison (1983); and Claudia Nichols, "Olympia Brown: Minister of Social Reform." Occasional Paper (Unitarian Universalist Women's Heritage Society, 1992). The Universalist Historical Society issued Olympia Brown: A Centennial Volume Celebration Her Ordination and Graduation in 1863 (1963). See also E. Larkin Brown, "Autobiographical Notes," edited by A. Ada Brown. Michigan Pioneer and Historical Collections (1905). Short biographies are also available in Famous Wisconsin Women, volume 3 (1973); Catherine F. Hitchens, Universalist and Unitarian Women Ministers, a special issue of the Journal of the Universalist Historical Society (1975), and Dorothy May Emerson, editor, Standing Before Us: Unitarian Universalist Women and Social Reform, 1776-1936 (2000).

Article by Laurie Carter Noble - posted May 28, 2001All material copyright Unitarian Universalist History & Heritage Society (UUHHS) 1999-2016

votre commentaire

votre commentaire

-

Par unitarien le 22 Mai 2016 à 11:43

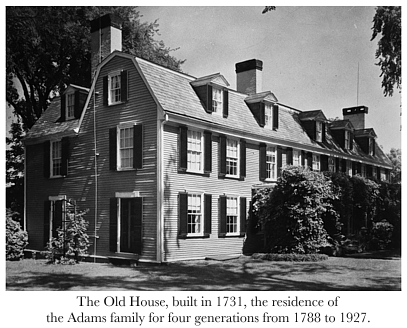

Henry Brooks Adams

and Marian Hooper “Clover” Adams

The journalist, historian, novelist, Henry Brooks Adams ( February 16, 1838-March 27, 1918) was the son of Civil War diplomat Charles Francis Adams and Abigail Brooks Adams. His grandfather, John Quincy Adams was the sixth President of the United States.

Henry Adams was christened by his uncle Nathaniel Langdon Frothingham, minister of Boston's First Unitarian Church. His formal education began in Boston, Massachusetts and continued in rural Quincy and at the Boston Latin school. He graduated from Harvard where he had family connections. His grandfather had taught rhetoric, his father was a board member, and his uncle Edward Everett had been president. Most Harvard faculty members, at that time, were Unitarian. After graduation in 1858, Henry went to Germany to study law but had problems with the language so he decided to travel instead. During his two years in Europe he interviewed Garibaldi in revolutionary Italy and he wrote newspaper articles as a correspondent for the Boston Courier. He returned to Boston on the eve of the Civil War in 1860 and tried to study law with Judge Horace Gray. His congressman father rescued him by making him his secretary. Henry continued his newspaper reporting, writing anonymously for the Boston Advertiser. When Congressman Adams was appointed United States Ambassador to England, Henry served as his father’s official secretary. For a while he sent news dispatches to the New York Times but stopped, fearing he would be discovered and charged with conflict of interest. The Adams' Unitarian acquaintances in England were: Charles Dickens, Harriet Martineau, and geologist Sir Charles Lyell. He reviewed Lyell’s Principles of Geology for the North American Review. Henry was in England for the duration of the Civil War.

He returned to Boston on the eve of the Civil War in 1860 and tried to study law with Judge Horace Gray. His congressman father rescued him by making him his secretary. Henry continued his newspaper reporting, writing anonymously for the Boston Advertiser. When Congressman Adams was appointed United States Ambassador to England, Henry served as his father’s official secretary. For a while he sent news dispatches to the New York Times but stopped, fearing he would be discovered and charged with conflict of interest. The Adams' Unitarian acquaintances in England were: Charles Dickens, Harriet Martineau, and geologist Sir Charles Lyell. He reviewed Lyell’s Principles of Geology for the North American Review. Henry was in England for the duration of the Civil War.

Returning to the United States, Henry Adams took up journalism and political reform. Articles he wrote appeared in the recently founded Nation and the New York Post. He advocated revenue reform and associated with those who had similar concerns in Washington. His hopes for President Grant were disappointed. Although disappointed politically, he enjoyed the informal Capitol life. The Edinburgh Review published his articles about corruption bringing him public attention.

Harvard reform President Charles W. Eliot appointed him assistant professor of medieval history in 1870. He usually socialized with younger Cambridge men, John Fiske, and Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., but he also visited the Ephraim Gurney household. There he renewed his acquaintance with Miss Marian Hooper, also known as Clover. Her sister was the wife of Harvard Dean Ephraim Gurney. It was Gurney who later hired Adams as North American Review editor.

Adams had met his future wife Marian Hooper (September 13, 1843-December 6, 1885), in 1866 when she was traveling in England with her father ophthalmologist Robert William Hooper. Her mother Ellen Sturgis Hooper, had been a minor poet and Transcendentalist. The Hoopers devoted themselves to philanthropy, art, and the education of their three children. Marian studied at Elizabeth Cary Agassiz’s Cambridge school. Dr. Hooper owned a King’s Chapel pew, while his wife attended James Freeman Clarke’s radically experimental Church of the Disciples, Boston. Marian’s grandparents entertained Emerson, and her mother and Aunt Caroline attended Margaret Fuller’s 1839 Conversations. They also contributed poetry to the Dial, the Transcendentalist journal. Clover’s mother wrote “Dry Lighted Soul,” dedicated to Ralph Waldo Emerson.

Henry and Marian were married on June 27, 1872 at the Hooper home in Beverly, Massachusetts by Rev. Charles Edward Grinnell (1841-1916), an 1865 Harvard Divinity School graduate. Adams called Grinnell “a jolly young fellow of our set.” Traveling to Europe following their wedding, they visited Henry’s father in Geneva where he was negotiating Civil War claims with the British. Henry and Clover proceeded to Berlin where her Unitarian cousin George Bancroft, U.S. Minister to Germany, introduced him to European historians and legal scholars.

Returning home after their honeymoon, Henry resumed his duties at Harvard in 1873. He was one of the first professors to teach using seminars. His Documents Relating to New England Federalism(1877), two biographies, John Randolph (1884) and The Life of Albert Gallitin (1879), and the nine volume History of the United States During the Administrations of Jefferson and Madison (1889-91) grew out of his graduate courses. His theme was the growth of America. The steamboat represented American power, as the dynamo would come symbolize a latter era. Chaffing at narrow academic life and clashing with the North American Review staff, he resigned his posts in 1877 and moved to Washington, D.C. to concentrate on writing.

Marian Hooper Adams was reared a Unitarian but became skeptical in later life. She was always loyal to Emersonian naturalism and never lost her social conscience. She was concerned for Native Americans and she was involved in her family's work with the Freedmans Bureau providing education for freed slaves. She said she wanted “to overcome prejudices,” but she often expressed contradictory preferences. She liked Italians compared to Germany’s “beer-drinking warriors.” She liked the Spanish while overlooking the social decay and corruption in Spain. She helped Henry with his writing but lacked ways to express her social concerns after their move to Washington, D.C. Clover was also a feminist. She and her cousin Elizabeth Bancroft shared an interest in the unconventional author George Sand. Although Henry favored education for women he questioned their abilities. Nevertheless, Clover studied Greek and Portuguese and backed her sister’s efforts to establish the Harvard annex that became Radcliffe. Clover softened Henry’s view of women and education. She was eager when women could vote for the first time in the 1879 school committee elections.

Clover’s Lafayette Square salon, across from the White House made her famous. John Hay, former Lincoln secretary and diplomat; Hay's wife Clara; and Clarence King, a geologist; made up their circle of friends known as the “Five of Hearts.” Mrs. Adams other interests included riding and portrait photography. She worked with photographic chemicals and darkrooms, processing her own pictures. She photographed her husband's parents and her portraits of Lincoln’s biographer John Hay and historian George Bancroft were significant. Although the Adamses didn't have children, she was a loving aunt to her five nieces, writing them stories, building them playhouses, and caring for them. Henry always had toys for little visitors.

Clover Adams was a literary model for her husband and for Henry James, a member of their Washington, D.C. circle. James shared Clover Adams Transcendentalist heritage. His Portrait of a Lady (1881) followed a visit with the Adamses. Protagonist Isabella Archer shares much of Clover’s personality. The despicable Gilbert Osmond characterizes Isabella saying, ". . . her sentiments were worthy of a radical newspaper or a Unitarian preacher.”

In addition to his historical writing, Henry Adams produced two novels, Democracy (1880) and Esther (1884). Like his wife Clover, the widowed Madeline Lee in Democracy, arrives in Washington, D.C. after a life of philanthropy. She organized a salon like Mrs. Adams. Writting under the name of Francis Snow Compton, he portrayed his wife again in Esther. He finished the book just before Clover’s death. Instead of the political corruption of Democracy, the novel concerns religion and its clash with science.

Clover took her own life by swallowing photographic chemicals on December 6, 1885, a few months after her father died. Her family sent for Unitarian minister Edward Hall, and she was interred in Rock Creek cemetery. There may have been a hereditary basis for her death. Even by the standards of upper class society her family was inbred. Her aunt died by her own hand. Her brother and sisters all attempted suicide. They had planned to go to Japan together after the first half of his monumental history of the Jefferson and Madison years was finished. As a tribute to her memory, he made the trip with his friend, artist John LaFarge as his traveling companion. Before leaving, he chose Augustus Saint-Gaudens, whose work Clover appreciated, to create an enigmatic memorial bronze sculpture in Rock Creek Cemetery where she was buried.

They had planned to go to Japan together after the first half of his monumental history of the Jefferson and Madison years was finished. As a tribute to her memory, he made the trip with his friend, artist John LaFarge as his traveling companion. Before leaving, he chose Augustus Saint-Gaudens, whose work Clover appreciated, to create an enigmatic memorial bronze sculpture in Rock Creek Cemetery where she was buried.

He went to the Polynesian islands in 1890, and in Samoa, he met Robert Louis Stevenson who sent him to Tahiti with an introduction to the pretender to the leadership of the Teva clan, Tati Salman. They adopted Adams and John Lafarge into their clan, which also had ethnic Jewish members. Adams recorded the memoirs and genealogy of Tati’s sister, the divorced former Tahitian Queen. Proceeding on toward Europe, Adams and LaFarge stopped in Ceylon, now Sri Lanka, where under a descendant of Buddha’s Bo Tree, Adams meditated for a half hour. Skeptically he said he left “without attaining Buddhaship.” Like other Bostonians and their contemporary Unitarian counterparts, however, he felt the lure of the East.

Even with much traveling, Adams finished his South Sea Memoirs of Marau Taaroa, Last Queen of Tahiti (1893). It documented Imperialist damage to native people. He did not include this period in his Education of Henry Adams. The American Historical Association chose him president in absentia at their 1894 meeting, the same meeting where Frederick Jackson Turner read his famous paper on the frontier theory.

Following the financial catastrophe of 1893 Adams had to help straighten out family affairs. He entered into dark speculations with his brother Brooks Adams about the Dreyfus affair and other international plots. In a limited number of his very private letters he made the word “Jew” synonymous with bankers and captialists. He echoed British and American populist rhetoric. Earlier as a historian, however, he had thought Jews were slighted. The historians’s sister Louisa had married Charles Kuhn, a Jew, and they got on well together. During their marriage, the Adamses had Jewish friends. In his youth, Adams tried to use his connections to help an American Jewish family who were badly treated in their native Germany. He even imitated Disraeli’s political novels. Also in the 1890’s, he sympathized with secular Jews including Elsie de Wolfe, his “niece in wish.” He also became good friends with Bernard Berenson, the art critic. He characterized Edouard Drumont’s views as “anti-semitic ravings.” He finally said that he was undecided about the Dreyfus case. While deeply worried about the threat to France from the Dreyfus scandal, he genuinely desired justice. He also backed away from his conspiratorial theories after a good deal of research. He remained, however, anti-capitalist. His greatest fury was reserved for French anti-Semites and he was prepared to join the anarchists in their attack on them. During the same time, he feared tropical people would overwhelm the northern hemisphere, although he had written sympathetically about the Tahitians and championed the cause of Cuba. He did not discuss this period in his Education of Henry Adams. He was a complex human being. Privately, and in a limited way he had used very, injudicious language.

Adams visited Cuba in 1894. Sympathy for the Cuban people led him to support the Cuban revolution. Cuban exiles met at the historian’s home across from the White House and planned delivery of arms and supplies. In a paper he wrote for the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, he encouraged United States intervention. After President McKinley’s assassination, Theodore Roosevelt invited him to the White House. The new Secretary of State, his friend John Hay, conferred with Henry and filled the Adams' house with dignitaries. History remembers Hay, Lincoln's Secretary and Secretary of State (1898-1905) as the architect of the Open Door Policy and the Hay-Pauncefote Treaty authorizing a Central American canal. By the turn of the century, however, he was an anti-imperialist ready to free the Philippines. As the new century began he feared Russia and Germany.

Disgusted by the present, Henry retreated into medieval study. He loved the French cathedrals and their windows. In his Mont Saint Michele and Chartres: A Study of Thirteenth-Century Unity Uncle Henry guides his imaginary nieces through three centuries of the middle ages. Adams chose the thirteenth century to measure his fin de siecle world. He gave privately printed copies of Mont Saint Michele and Chartres as New Year gifts in 1905.

The church and devotion to the Virgin unified the medieval period, but where was continuity in his own time and what was the direction of history? He considered these questions in his next works. The Education of Henry Adams (1918) was privately printed and sent to friends. He had not mentioned Clover at all. Adams lived from the oil lamp era, through the Civil War and into the era of electricity, x-rays, and radium. He contrasted his time with the medieval age in the chapter “The Dynamo and the Virgin” in The Education of Henry Adams. Electricity and the great dynamos that generated it at the World's Fairs captured his imagination. As he saw it, in the Middle Ages people had worshiped the Virgin and were devoted to her churches while twentieth century people worshiped the humming machines. Instead of uniting people, however, this twentieth century worship divided them. He developed an historical theory of devolution in the final chapters of his biography. He longed for the “laws of Nature and Nature’s God” to guarantee the course of morals and good government.

Henry Adams literary work continued through his final years. When his friend Secretary of State Hay died, Adams edited his letters and published them in 1908. In July, Adams had a stroke in Paris; that November he drew up his will instructing that he should be buried in an unmarked grave near Clover. Dissatisfied with the “Dynamic Theory of History” in his The Education of Henry Adams, he sent two papers, “Rule of Phase Applied to History” in 1909, and “Letter to American Teachers of History” in 1910 to his colleagues. Unlike the Darwinists whom he read after the Civil War, Adams proposed a law of social decay. In spite of the elaborate mathematics in these papers, however, his arguments were mostly supported by analogies. He complained to Brooks about his critics saying, “The fools begin at once to discuss whether the theory was true.” Following the death of his young friend, poet George Cabot Lodge, he published a short biography of the poet in 1911. In spite of his dark mood Adams continued to read and supported archeological excavations and the search for prehistoric humans in the French Dordogne caves.

In 1912 the Titanic sank. Adams, who had booked tickets for its first return voyage from New York to England was shaken. Shortly after returning home to Washington, D. C., he had a stroke but in spite of his gloom and frustration with William Howard Taft’s administration, he recovered. The next year Adams finally published a commercial edition of Mont Saint-Michel and Chartres (1913).

Just before the Great War, Henry was in France with his nieces looking for medieval songs. When war came, he gathered them and managed the last trains and boats out of France. Returning to the United States, he even made a last return to Beverly Farms to his 1876 house abandoned after Clover’s death. He reflected, “Behind all the killing comes the great question of what our civilization is to do next.”

Toward the end of his life he said that “Unitarian mystic” best described his religious views. He returned home to Washington, D.C. Where he died on March 27, 1918. He was buried with Clover in a grave unmarked except by the famous statue he had commissioned. In 1919, he received the Pulitzer Prize posthumously for The Education of Henry Adams. The same year his brother Brooks Adams saw Henry’s last papers through the press as Degradation of the Democratic Dogma.

The principal archival repository for the Adams family is the Massachusetts Historical Society in Boston, Massachusetts. Some letters of Henry Adams are in the South Caroliniana Library at the University of South Carolina in Columbia, South Carolina. Material relating to the family and Harvard can be found at the Harvard University Archives in Cambridge, Massachusetts. In addition to the books by Henry Brooks Adams mentioned in the text, a number of collections of letters are available including: Henry Adams and His Friends: A Collection of His Unpublished Letters, ed. Harold Dean Cater, (1970); Letters of Henry Adams 1858-1891, ed. Worthington Chauncey Ford, (1930); and Letters of Henry Adams 1892-1918, ed. Worthington Chauncey Ford (1938). A collection of shorter pieces are in Edward Chalfant, Sketches for the “North American Review,” (1986). A bibliography of Henry Brooks Adams works can be found in Charles Vandersee, “Henry Adams: Archives and Microfilm,” Resources for American Literary Studies (1979).

His autobiography, The Education of Henry Adams (1918) is to some extent fictional, a better history than biography. Edward Chalfant and Ernest Samuels, two leading Henry Adams scholars, have written a number of books on Adams. For extended biographical coverage consult the three volume biography by Edward Chalfant, Both Sides of the Ocean A Biography of Henry Adams: His First Life 1838-1862, (1982); Biography of Henry Adams: His Second Life 1862-1891, (1994); andImprovement of the World: His Last Life, 1891-1918 (2001). Another three volume biography is Ernest Samuels, Henry Adams: The Young Henry Adams, (1967); Henry Adams: The Middle Years, (1958); and The Major Phase, (1964). For coverage of his Washington, D.C. Years see Patricia O'Toole, The Five of Hearts: An Intimate Portrait of Henry Adams and His Friends, 1880-1918 (1990).

For more on Marian Hooper Adams see Natalie Dykstra, Clover Adams: A Gilded and Heartbreaking Life (2012); Eugenia Kaledin, The Education of Mrs. Henry Adams, (1981); and Ernest Samuels, “Marian Hooper Adams” in Notable American Women 1607-1950, ed. Edward T. James, (1971). Letters by Marion Hooper Adams can be found in, The Letters of Mrs. Henry Adams, ed. Ward Thoron (1936). A critical appraisal of Henry Brooks Adams as a writer and historian is found in Gary Wills, Henry Adams and the Making of America (2005). A history that explores the relationships among the extended Adams family is Francis Russell, Adams, an American Dynasty (1976).

Article by Wesley V. Hromatko, D.Min. - posted March 28, 2012All material copyright Unitarian Universalist History & Heritage Society (UUHHS) 1999-2016

2016  21 commentaires

21 commentaires

-

Par unitarien le 5 Mai 2016 à 17:45

Peter Charadon Brooks Adams

Peter Charadon Brooks Adams (June 24, 1848-February 14,1927) was a lawyer, historian, and writer, who served as an informal adviser to President Theodore Roosevelt. Although reared Unitarian, he was agnostic for many years. Late in life he returned to the Unitarian fold at the family church in Quincy, Massachusetts. Named for his grandfather Peter Charadon Brooks, he was called Brooks at his grandfather's suggestion.

He was the youngest son of Abigail Brooks Adams and Charles Francis Adams, Sr. His mother was the youngest daughter of wealthy Unitarian Peter Charadon Brooks and Anna Gorham Brooks.President John Quincy Adams (1767-1848) was his grandfather and President John Adams (1735-1826) a great grandfather. His father, a diplomat, legislator, and writer was nominated for Vice President on the Free Soil ticket the year Brooks was born. Brooks Adams was baptized by Nathaniel Frothingham, the Unitarian minister at First Church of Boston, Massachusetts. His mother and father, conscientious parents, took him to the new Sunday school at First Church where his father sometimes taught. Later his father was the Sunday school superintendent at their summer church in Quincy, Massachusetts. His parents worried about Brooks during his childhood; he seemed too active, was often inattentive, and sometimes made scenes in public. He collected stamps with a single-minded zeal that often interrupted family life, and he had reading and spelling problems that made his mother despair. In spite of these difficulties, his parents took young Brooks to places like the Smithsonian. He attended Columbia College in New York City, as did his sister Mary.

Brooks Adams was baptized by Nathaniel Frothingham, the Unitarian minister at First Church of Boston, Massachusetts. His mother and father, conscientious parents, took him to the new Sunday school at First Church where his father sometimes taught. Later his father was the Sunday school superintendent at their summer church in Quincy, Massachusetts. His parents worried about Brooks during his childhood; he seemed too active, was often inattentive, and sometimes made scenes in public. He collected stamps with a single-minded zeal that often interrupted family life, and he had reading and spelling problems that made his mother despair. In spite of these difficulties, his parents took young Brooks to places like the Smithsonian. He attended Columbia College in New York City, as did his sister Mary.

When his father went to England to represent the United States during the Civil War, Brooks went along, attending Wellesley House, a British public school. Although Brooks won prizes at Wellesley House in most subjects and acquired an English accent, he wasn't ready for Harvard which required Greek and Latin. Returning home in 1865, he was tutored by Professor Ephraim Whitman Gurney. By the fall of 1866, he passed the Harvard entrance examination and enrolled. The curriculum had changed little in the ten years since his brother Henry Adams had attended. Brooks did not enjoy his studies, except for Ephraim Gurney’s course on Rome, nor did he apply himself. In time though, he matured overcoming most of his childhood problems. His brothers John and Charles disliked him while Henry treated him well. Brooks did nothing to improve his relationship with Charles when he charged a wine bill to his older brother. At Harvard, Brooks went out for rowing, and was the first Adams to get an invitation to join the prestigious Porcellian club. Following a trip west after graduation, Brooks decided to study law at Harvard Law School. He roomed with his brother Henry in Wadsworth House.

His father, Charles Francis Adams, Sr. returned to the diplomatic service in 1871 to negotiate Civil War damage claims against Great Britain over the building of the Confederate warship Alabama. President Grant opposed the appointment, but Secretary of State Hamilton Fish wanted Adams. When his father went to Geneva, Switzerland to take his place on the arbitration commission, Brooks, interrupting law school, went with him. His mother Abigail could not go. In 1870, his sister Louisa Catherine Adams, also in Europe, died in an Italian carriage accident. His father returned home when his mother became ill, but Brooks remained in Paris, not coming back to the United States until 1872. Once home, he studied law on his own, passed the bar, and opened a practice. In his free time he pursued his interest in reform including corresponding with journalist and poet William Cullen Bryant and other movement leaders. He wrote articles for the North American Review—which his brother Henry Adams edited—and The Atlantic Monthly. He ran for the General Court in 1877 but lost by two votes. In 1880 he had a breakdown that may have been caused by overwork. After recuperating in Florida he visited Henry who was living in Washington, D.C. In better health, Brooks returned to Quincy to care for his aging parents.